In an age of trade wars, armed conflict, pandemics and climate change, too little attention is being paid to the vulnerability of the global food system. The UK is not immune to the risks, which could lead to food shortages and civil unrest in the next ten to 50 years.

Food systems around the world face a variety of risks. It is in this context that the UK government launched its much anticipated food strategy in July 2025, with a vision of ensuring ‘improved resilience of the supply chain, with reduced impact of shocks and chronic risks on access to healthy and sustainable food’. But what risks does the food system face and how vulnerable is the UK?

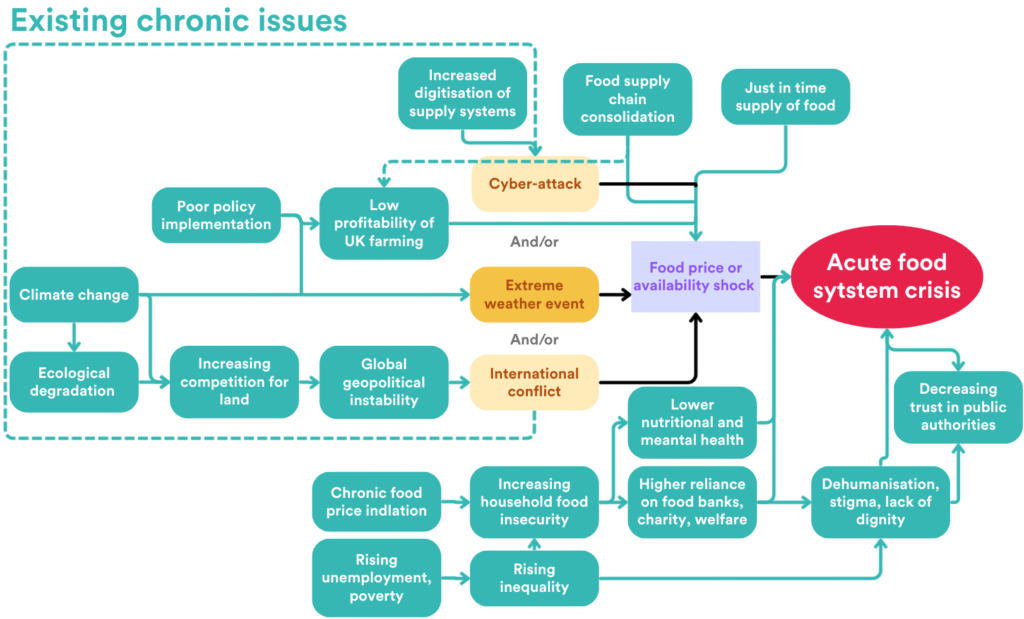

Research published in 2023 assesses the major risks to the UK’s system for producing and distributing food (Jones et al, 2023) . The authors find that these risks, which include extreme weather, cyber-attacks and pathogens, could lead to food shortages and civil unrest in the next ten to 50 years (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Risks associated with the UK food system over 10 and 50 year periods.

10 year horizon

50 year horizon

Source: Jones et al (2023)

Note: Backcasting map of possible routes to the Societal Event (right of each panel) from the underlying cause (left) via the Food System Scenario type (centre). Themes not voted on by all participants are shown in lighter boxes.

Now, just two years later, we can see that many of these risks have already begun to happen around the world. Below are a few of them.

Solar storms and GPS

A 2024 solar storm produced some of the strongest auroras in 500 years and scrambled GPS-guided tractors across the US Midwest. There were reports of vehicles lurching off course ‘like they were demon possessed’ and farmers having to stop or take control manually. The planting season was disrupted. Roughly half of US farmers need GPS to guide their tractors, so such events can have significant impacts.

Extreme weather

Drought in southern Africa in 2024 ruined about half of Zimbabwe’s maize crop, resulting in regional shortfalls, trade restrictions, increased imports and inflation. In Brazil, heavy rain and floods reduced up to a quarter of soybean yields.

Trade and tariffs

The US government has implemented tariffs on products imported from the UK and about 90 other countries, including major producers like Canada, China and Mexico. The United States imports almost a fifth of its food, so the tariffs will have an inflationary pressure on food prices within the country.

Certain products are expected to be affected particularly acutely, such as seasonal fresh produce, which is dominated by Mexican imports. Analysts are predicting up to 25% price increases this autumn for such products. Beyond the United States, the tariffs create an uncertain global trading environment with supply chains shifting to respond, resulting in volatile prices across food markets.

War and conflict

The US government also seems to fluctuate dramatically in its commitment to military support for Ukraine, the ‘breadbasket of Europe’, where there has already been an 80% drop in wheat exports since the start of the Russian invasion. Global food prices spiked by a third during the first few months of the conflict, and war continues to threaten global food security.

Transport and infrastructure

Elsewhere in the United States, strikes by port workers have further strained supply chains. Similarly, a national grid breakdown in Cuba in 2024 created refrigeration problems that caused food shortages due to spoiling.

Cyber-security

In 2025, a cyber-attack on United Natural Foods, a major North American supermarket distributor, stopped deliveries to 30,000 grocery stores. The US government is currently legislating the Farm and Cybersecurity Act to direct resources to address the vulnerability of the sector to such risks.

Migration

Internally, both the UK and the United States are trying to curb migration. This will affect the agricultural sector by creating labour shortages, which may leave crops unharvested or unplanted, warehouses and restaurants unstaffed, and food undelivered.

Subsidies and policy change

In the UK, farmers are also grappling with changes in subsidies, such as the end of the sustainable farming incentive, and taxes, as well as the implications of a transition to net-zero emissions of carbon dioxide.

How worried are food industry insiders?

These types of events could mean a simultaneous failure of key parts of the food system. This has the potential to limit the supply and increase the cost of food in the UK and worldwide. Similar historical shocks to the system show how disruptive these risks are when they materialise, with shocks to the affordability or availability of food leading to protests, civil unrest and, where existing social tensions are high, changes in government.

Traditionally, the UK government has not seen food risk as significant. But the country’s food system is not immune to these risks and it is seen as vulnerable by many industry insiders.

In a recent memo published online, 20 food industry executives writing under anonymity said that they were worried about urgent risks to the UK food system from climate change, failing soil health and mismanaged supply chains. The authors blame a culture of ‘short-termism’ in the sector, expressing concerns that the sector does not collaborate to develop long-term strategies, resulting in a lack of appropriate measures to mitigate the risks to food production.

How should policy-makers respond?

Policy-makers in the UK and further afield should focus on building food system resilience to these growing uncertainties. To allow them to do so, researchers need a better understanding of the various links and leverage points associated with how food is produced and distributed in the UK and around the world.

One way to think about this is to assess the three Rs of food system resilience – robustness, recovery and re-orientation. The robustness of a food system is its ability to absorb shocks or stress and keep functioning. If it isn’t robust, it can’t rapidly recover or ‘bounce back’ from a shock (such as a drought). If it can’t recover, it might not be able to transform such that it is more robust or can recover faster in the face of future shocks.

Fortunately, there are several useful ways to calm the coming storm. For example, we can model food systems on computers or learn from ‘serious games‘ with decision-makers in government and industry.

Serious games are a policy tool that helps to inform future government policy as well as business strategy by testing potential interventions that increase the resilience of the food system. These range from measures like agro-forestry/agro-ecology, diet changes, parametric insurance, improved cyber-security, local community food hubs, regional storage facilities and coordination across national delivery, to bold measures such as a ‘right to food’ policy.

As food systems are highly complex and face many risks, it is challenging to model them in full. Serious games can help to reveal the widest possible view of food systems and allow policy-makers, business leaders, farmers and other key parties to see more clearly where and how food systems can be made more resilient. Serious games have been used extensively by governments to plan interventions in war-time scenarios, but they are now being developed for a wider set of challenges.

UK research councils recognise the urgency of food system risks. To meet this challenge, they are funding a collection of projects on food system resilience, such as Backcasting to Achieve Food Resilience in the UK (BAFR), which includes a serious game and a large quantitative model to bring together a wide range of experts from across the UK food system (see Figure 2). Projects like BAFR will play a substantial role to play in making the UK food system more resilient to the many risks manifesting in the world today.

Figure 2: High level systems diagram of the UK food system

Source: Bridle et al, 2025

Given this context, the commitment in the UK’s new food strategy to improving the resilience of the country’s supply chains is welcome. Importantly, as highlighted through the myriad of risks we have mentioned here, the focus on working across the whole of government to address the interconnectedness and interdependence of the food system is the only way to deal with the challenges the country faces. The national food strategy is only the first step is tackling this problem – the real work starts now.

Acknowledgements

BAFR-UK has received £2,048,461 in funding from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), part of UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). The funding is from the UKRI Strategic Theme on Building a Secure and Resilient World (BSRW).

The authors thank Angelina Sanderson Bellamy, Sarah Bridle, Elena Cini, Dan Crossley, Peter Falloon, Rosemary Green and Maryla Hart for their help with this article.

Where can I find out more?

- Scoping potential routes to UK civil unrest via the food system: results of a structured expert elicitation: study by Aled Jones, Sarah Bridle and colleagues published in Sustainability in 2023/

- Memo to investors, directors, owners and creditors: Inside Track message from UK food industry executives, April 2025.

- Just in case: 7 steps to narrow the UK civil food resilience gap: 2025 report by Tim Lang and colleagues for the National Preparedness Commission.

Who are experts on this question?

- Sarah Bridle

- Henry Dimbleby

- Aled Jones

- Tim Lang

- Christopher Lyon

- Elta Smith