Over the past few centuries, Britain has undergone three periods of major agricultural change. These revolutions in farming practice are closely tied to long-term economic development and highlight the country’s journey from pre-industrialisation to post-war recovery.

Changes in farming practices are bound tightly to Britain’s economic history. The ways in which farmers have managed their land, looked after their livestock or crops, and brought food to market has evolved dramatically over the years. This has shaped – and been shaped by – the country’s economy. To understand Britain’s economic history, we must understand its food.

Three distinct phases of rapid agricultural changes – often called ‘revolutions’ – took place in Britain starting in the early 18th century.

The first phase – encompassing the mid-18th to early-19th centuries – was characterised by the enclosure of open fields and the pioneering initiatives of a small number of ‘agricultural innovators’. This period is widely considered to be an essential pre-requisite in facilitating Britain’s industrial revolution.

The second period of change – covering the end of the French and Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815) to the 1880s – transformed farming from being what was, in essence, an extractive self-contained mode of production to a system resembling manufacturing.

The third phase of unprecedented agricultural development covers the state-directed food production campaign of World War II and its immediate aftermath. During this period, maximising domestic food production was the overriding policy objective.

This article explores the relative importance of these three phases in Britain’s economic development.

The classic agricultural revolution: enclosure

During the industrial revolution, agriculture played a critical role in Britain’s economic transformation. The rapid development of agriculture was an essential precursor to industrialisation during the 18th century. It not only facilitated an increase in the domestic supply of food, but also enabled the rapidly increasing population to move from what was essentially subsistence farming to work in manufacturing enterprises. This allowed the country to become the world’s leading industrial nation by the early decades of the 19th century (Allen, 2014).

One of the most salient features of this first transformation was the re-organisation of land tenure through the enclosure of open fields. In this process, the communal system of farming – in which villagers had access to strips within open fields for arable cropping and commons for their livestock to graze – was replaced by an enclosed system, which came under the jurisdiction of an individual farmer.

This transformation enabled the use of new and more productive techniques such as the ‘Norfolk four-course rotation’ (a system in which different crops like wheat and turnips were grown on the same land over a sequence of years). The system replaced the traditional three-field rotation of cereals interspersed with fallow.

The cultivation of clover, which has nodules on its roots that allow it to fix nitrogen from the atmosphere, is estimated to have accounted for about half of the increase in crop yields that occurred between the 14th and early-19th centuries (Allen, 2008). The popularisation of growing turnips provided a valuable source of feed for cattle and sheep during the bleak winter months.

This was accompanied by the selective breeding of livestock, pioneered by Robert Bakewell (according to contemporary accounts). He was one of the first farmers to breed both sheep and cattle specifically for meat, instead of for wool or work.

It has also been argued that the development of these agricultural innovations was not the result of pioneering initiatives by a limited number of heroic individuals. Instead, analysis by Mark Overton reveals that many of the innovations or practices that are viewed as constituting an 18th century revolution in agriculture were either insignificant or occurred much earlier (Overton, 1996).

What is clear is that the enclosures that had been taking place since the Middle Ages were confined mainly to the lowland areas of England, found in a broad band running diagonally across the country – from Yorkshire and Lincolnshire to the south, taking in parts of Norfolk and Suffolk, Cambridgeshire, large areas of the Midlands and most of south-central England. From 1760 to 1870, the re-organisation from common to enclosed land involved about seven million acres (about one-sixth of the area of England), via roughly 4,000 separate acts of parliament (Overton, 1996).

The second agricultural revolution: increased industrialisation

The second agricultural revolution – which is considered to have taken place between 1815 and 1880 – broke the closed-circuit system, encouraging farmers to use a variety of non-farming inputs, such as chemical fertilisers, in their work. In doing so, it made the operations of the farmer much more like those of the factory owner (Thompson, 1968).

This second period of transformation reflects an enhanced understanding of the importance of natural manures and, to a lesser extent, chemical fertilisers as a means of increasing the fertility and productivity of arable crops and grassland. The phase also included the increased use of protein-rich oil-seed cakes (a by-product of the industrial sector) to feed cattle, producing nutrient-rich farmyard manure, which then enhanced crop yields (Thompson, 1968).

In effect, these changes mark the transition from what was essentially an organic system of farming to a system that used resources originating from outside the agricultural sector. This was accompanied by considerable investment in drainage, buildings and mechanisation. In the case of mechanisation, for example, the widespread adoption of the binder (a machine for cutting grain and collecting it into bundles) in place of the scythe meant that by the late 1870s, two-thirds of cereal crops was harvested by machine.

In a similar way and by the same date, three-quarters of threshing (the process of separating grains like wheat from their stalks) was being undertaken by steam-powered threshing drums (Collins in Mingay, 1981). By the last few decades of the 19th century, new technology had taken over much of the typical farm.

The third agricultural revolution: the war economy

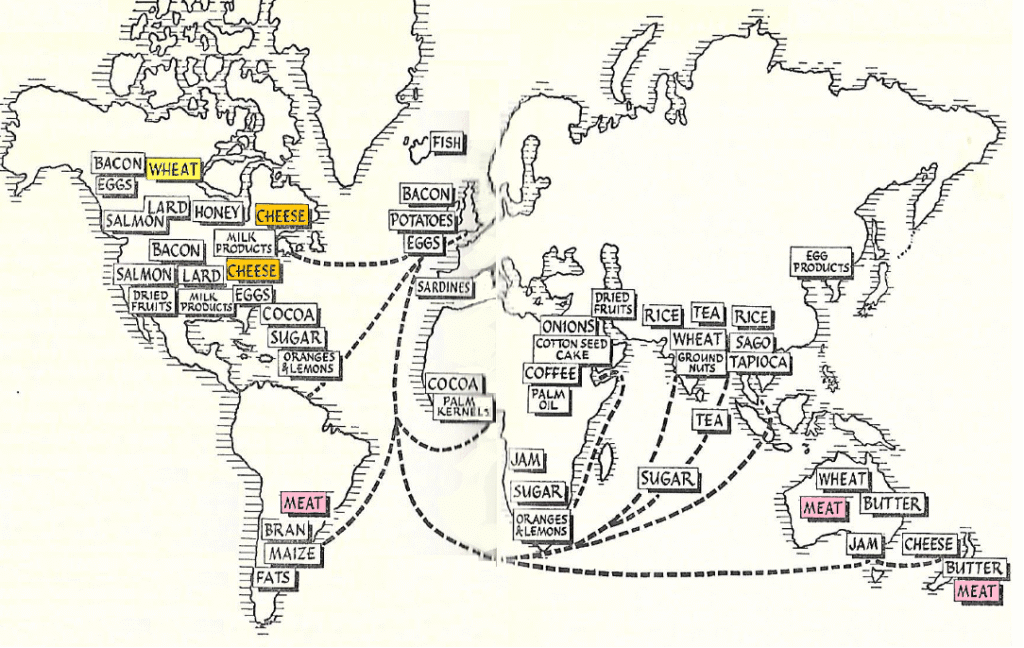

By the late 1930s, the looming threat of a war meant that Britain was in a very precarious position in terms of food security (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Food imports to Britain in the 1930s

Source: Woolton (1959)

In 1938, 70% of the cash value of the food consumed in Britain came from overseas – around 23 million tonnes of shipping space for food, fodder and fertiliser. No other European country was anywhere near as reliant on food imports as Britain, its nearest rival being Switzerland whose food imports amounted to ‘just’ 35% of its total consumption.

For policy-makers at the time, it was imperative that Britain became more self-sufficient. It did so by converting pastureland into space for arable farming. The latter produced considerably more calories per acre and was considerably cheaper than any of the other options. But this massive shift towards arable cropping required an enforced reduction in livestock numbers, compounded by the wartime reduction in imported food (much of which was used to feed farm animals).

To coordinate the food production campaign at the local level, the government established a war agricultural executive committee (WAEC) for each county in England and Wales. The wartime strategy was to expand arable farming by promoting the ploughing up of grassland.

The achievements were outstanding: ‘by 1944 there had been, compared with pre-war production, a 90% increase in wheat, 87% in potatoes, 45% in vegetables and 19% in sugar beet’ (Ministry of Food, 1946).

But this wartime increase in production was primarily the result of the grassland ploughing-up campaign designed to increase acreage, as opposed to focusing on efforts to increase yields. Even so, the five million acre wartime increase in arable land surpassed that achieved during any previous period of agricultural development (see Figure 2). More available land meant more food.

Figure 2: Arable acreage in Britain, 1870 to 1960

Source: Best and Coppock (1962)

During this period, livestock production was deliberately curtailed by the state. The pre-war horse-based system of farming was rapidly replaced by mechanical power, usually in the form of tractors. On the eve of World War II, there were around 56,000 tractors in England and Wales. By the end of the conflict, the number had swelled to more than 180,000, mainly as a result of imports from America.

To facilitate the expansion of arable farming, which required more labour than land devoted to pastoral farming, Britain needed more agricultural workers. Following the exodus of farm workers into the armed forces, coupled with the opportunity for better-paid types of war work for non-combatants, it was necessary to supplement the existing labour force.

In addition to the establishment of the highly acclaimed Women’s Land Army, school children as well as prisoners-of-war (POWs) were mobilised to work the land. On average, one in every ten workers in British agriculture was a POW from 1941 to 1947 (Custodis, 2012).

These measures helped Britain to increase the production of arable crops more than any of the other nations embroiled in the conflict. Although countries such as Germany and Russia were less dependent on imported food prior to the outbreak of military hostilities, they were forced to endure a food crisis much worse than that experienced by Britain.

Peace did not bring an immediate end to food scarcity. Following the end of the war, shortages on an international scale meant that maximising agricultural production became an overwhelming policy priority (Martin, 2023). By 1947, world food production was still 4% below its pre-war levels.

In Britain, the restrictions of food rationing were considerably more draconian than they had been during the darkest days of the global conflict. In 1946, bread was rationed for the first time, while further restrictions were imposed limiting the amount of meat and cheese that was available.

There was also the need to increase domestic food production. The idea was to placate the electorate as well as to show that agriculture was being reformed in accordance with radical economic and social reforms (such as the establishment of the welfare state).

The outcome of this political mood was the 1947 Agriculture Act, which established a system of guaranteed prices intended to ensure stability as well as to promote improvements in productivity and efficiency for farmers. The act enshrined guaranteed prices for the main agricultural commodities during peacetime, as well as providing grants to promote infrastructure improvements.

To maintain the profitability of their businesses and, in turn, their standard of living, it was essential for farmers to become more efficient. It was imperative that they adopt a more productive and scientific approach to the way they farmed. This pressure led to the post-war transformation sometimes described as the ‘real agricultural revolution’ or the ‘modern agricultural revolution’ – a period of unprecedented increases in agricultural output and productivity, coupled with changes in the way that the land was farmed (Brassley et al, 2023).

These post-war productivity increases dwarf those of previous periods. Agricultural output trebled, with self-sufficiency rising from 40% to 60% between 1954 and 1973. In the agricultural sector, total factor productivity nearly doubled from the 1950s to the 1990s. Yields of arable crops increased up to three-fold and there were significant corresponding increases in the output and productivity of the livestock sector.

Again, technology played a major part in driving progress. It is widely accepted that these post-war increases were primarily the result of the widespread application of scientific and technical knowledge, and its assimilation by the farming community.

The innovations that facilitated this increase were not necessarily simply post-war developments, but often had their origins in the pre-war period. Milking machines, tractors and the use of silage were all features of British farming prior to the outbreak of the war. The distinguishing feature of the post-war period was not only the development of new productive farming methods, but also the way in which new systems of production were so rapidly assimilated by farmers. Adoption was critical in driving change (Martin, 2023).

Another major contributing factor in this third revolution was the newly established National Agricultural Advisory Service (NASS). One of the goals of NASS was to persuade farmers to adopt higher yielding varieties of cereals and grasses. Indeed, nearly 50% of the virtual doubling of yields that occurred after the war can be attributed to the work of geneticists and plant breeders directly employed by publicly funded plant breeding centres (Palladino, 2008). Making farms more productive often started with the seeds.

Conclusion

Whether these three phases of rapid agricultural development constitute separate distinct revolutions or are parts of an all-encompassing agricultural revolution spanning several centuries is a moot point. On a comparative basis, it may be tempting to argue that the changes that have taken place since the onset of World War II are the most profound: not only did the state-directed agricultural revolution during that conflict dwarf the achievements of previous two phases, but it literally saved the country from starvation and established modern agriculture.

But we should not underestimate the important role that the two earlier revolutions played in facilitating the transformation of Britain from an agrarian economy to an industrial economy. Collectively, these periods of rapid change reveal agriculture as a vital contributor to British economic development, and highlight its potential role in tackling contemporary challenges like climate change.

The three revolutions also reveal that realigning agriculture to cope with new challenges requires the efforts of pioneering entrepreneurial individuals, as well as the work of appropriate state agencies to ensure that the latest knowledge is effectively disseminated to and adopted by the farming community. The world will keep changing – and British farming must too.

Where can I find out more?

Wartime Farm: An eight-part historical documentary TV series in which the running of a British farm during World War II is re-enacted, first broadcast on BBC Two in 2012.

George Odlum, the Ministry of Agriculture and ‘Farmer Hudson’: A case study by John Martin of the way in which a pioneering dairy farmer was treated during World War II.

The Museum of English Rural Life: This collection at the University of Reading has a comprehensive set of online archival sources.

The Real Agricultural Revolution: The Transformation of English Farming 1939-1985: Book by Paul Brassley, Michael Winter, Matt Lobley and David Harvey, published by Boydell and Brewer.

British Agricultural Revolutions: The dissemination and assimilation of more productive methods: Study by John Martin, published in the Journal of the International Committee for the History of Technology in 2023.