Despite facing unprecedented sanctions on its energy exports, Russia continues to earn hundreds of billions of dollars a year from oil and gas – directly funding military aggression in Ukraine. While sanctions have had a noticeable impact, they have failed to end the war.

More than three years into the conflict in Ukraine and the Russian war machine grinds on. Much of the targeted country remains an active war zone and Vladimir Putin looks unlikely to halt his invasion any time soon.

At the onset of the war, Western countries were quick to mobilise, coming together with the aim of hobbling Russia’s economy through a programme of coordinated economic sanctions (including measures aimed at the Kremlin’s fossil fuel operations). But to date, the measures have failed to change Putin’s actions.

Several factors contribute to the limited effectiveness of international sanctions on Russian energy: deliberate loopholes in the sanctions regime, which allow Russian oil and gas to flow to Europe; a general hesitancy to tackle the volume of Russian exports and risk higher energy prices, which has been the key driver behind the creation of the G7+ oil price cap; and fundamental flaws in the way in which sanctions are imposed, such as the price cap, whose leverage has been diminished by the ‘shadow fleet’ and which is largely unenforceable.

The existing system is not broken beyond repair. But fixing it will require real political commitment. Considering Russia’s obvious lack of interest in any peace negotiations, more drastic measures should also be considered.

The effectiveness of energy sanctions: two sides of the same coin

There are at least two ways to answer the question of whether sanctions work when it comes to energy.

First, there is the positive one: sanctions on Russian fossil fuel exports, in particular crude oil and petroleum products, have cost the country more than $100 billion in export earnings since the embargo by the European Union (EU) and the UK took effect at the end of 2022 (see Figure 1). This is due to a wider discount on Russian oil export prices (versus the rest of the global market), as the country had to offer better contractual terms in order to find new buyers for the oil that could no longer flow to its primary export market of Europe.

Second, there is the not-so-positive answer: Russia earned $235 billion from exports of oil and gas in 2024 – 0.5% more than in 2023, and only 3.7% less than in 2021 and 1.3% less than in 2019 (see Figure 2). The only (recent) exceptions were 2022, when energy prices soared, and 2020, during the Covid-19 pandemic. Export earnings have clearly not been constrained sufficiently by energy sanctions.

This has immediate consequences for Russia’s ability to fund its war of aggression against Ukraine through sales of fossil fuels. Even though Russia largely taxes production and not exports, the lack of storage capacity means that the two are closely aligned. In 2024, oil and gas revenues reached 11.1 trillion roubles – the second highest level in the recent past (see Figure 3). This was supported by a weaker domestic currency and stable export volumes. These revenues fund close to 30% of Russia’s total budget expenditures.

Figure 1: Russian oil price and export losses

Source: IEA (International Energy Agency), KSE Institute, Kyiv School of Economics

Figure 2: Russian oil and gas export earnings, $ billion

Source: KSE Institute

Figure 3: Russian oil and gas budget revenues, trillion roubles

Source: Ministry of Finance of Russia

Challenge 1: deliberate loopholes

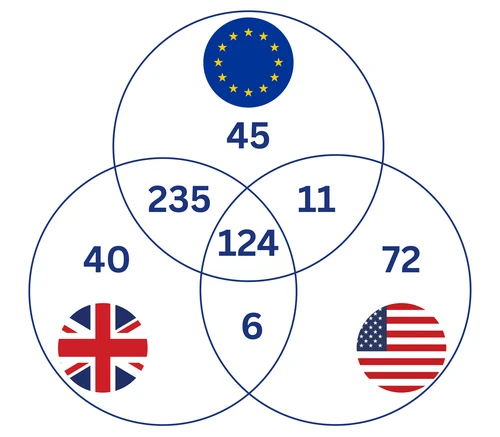

Several countries, including Australia, Canada and the United States, sanctioned imports of Russian energy just after the start of the full-scale invasion in February 2022. But these countries only accounted for a small share of Russia’s oil and gas exports at the time – just 3.7% in 2021 (see Figure 4).

Sanctions in this area did not begin in earnest until the EU (and the UK) imposed embargoes on Russian oil, including crude oil, in December 2022 and petroleum products in February 2023. In the meantime, Russia benefitted from soaring energy prices and generated sizeable inflows of foreign currency. This supported Russia’s macroeconomic stability during the first few months of the war.

Even after the oil embargoes had taken effect, there were – and are – many substantial loopholes in European sanctions on Russian energy, all of which are deliberate decisions due to specific political sensitivities or economic dependencies.

First, the embargo only applies to seaborne exports (that is, oil transported with ships). Pipeline oil remains entirely exempt.

Second, there are effectively no meaningful sanctions on Russian natural gas. Many European countries diversified their supplies as Russia attempted to blackmail Europe by cutting flows in 2022. But legally, nothing precludes them from reversing this decision. And two countries (Hungary and Slovakia) continue to import Russian natural gas unabated.

Third, EU imports of Russian liquified natural gas (LNG) are rising, increasing by 9% in 2024 compared with 2023 in volume terms.

Fourth, EU member states purchase a significant amount of petroleum products that are refined from Russian crude oil in third party countries, including India and Türkiye. This means that they are indirectly supporting Russia’s exports. With its 18th package of sanctions adopted in July 2025, the EU has now banned such imports.

Altogether, EU countries imported Russian crude oil and natural gas worth €22 billion in 2024, as well as roughly €5 billion in Russian oil-based petroleum products (see Figure 5).

Figure 4: Imports of Russian oil and gas in 2021, share by trade partner

Source: UN Comtrade

Figure 5: European imports of Russian fossil fuels in 2024, € billion

Source: CREA, Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air

Challenge 2: the decision to leave volumes untouched

Outright bans by Ukraine’s allies themselves have not had a meaningful impact. Unsurprisingly, their decisions to end purchases of Russian oil have led to a redirection of these volumes to other buyers, with India becoming the most important new destination.

This is partly because coalition countries made a deliberate decision not to take any steps to reduce the volume of Russian oil supplied to the global market. This was due to somewhat legitimate concerns about the impact of doing so on energy prices. Instead, they opted to (attempt to) reduce Russian export earnings via the price, implementing an innovative approach to doing so: the G7+ oil price cap (OPC).

In essence, the OPC states that Russian oil transported with the participation of service providers from G7+ jurisdictions must be sold at or below a certain threshold – set at $60 per barrel (bbl) for crude oil and $45/bbl or $100/bbl for different types of petroleum products.

Independent of the price cap’s effectiveness, this limits the potential impact of the sanctions from the start. Indeed, Russian oil export volumes have remained remarkably stable over the course of the last three years or so (see Figure 6). Research shows that the price cap played a much smaller role compared with the embargo when it comes to the reduction of Russian export earnings (see Kilian et al, 2024).

Figure 6: Russian oil exports, million barrels per day (MBd)

Source: IEA

Challenge 3: the deficiencies of the oil price cap

The chosen instrument to constrain Russia’s ability to pay for the war – the OPC – has not worked for two key reasons. First, the build-up of the ‘shadow fleet’ has dramatically reduced its leverage. Second, even where the price cap still applies, compliance has been negligible and enforcement extremely challenging due to the lack of reliable pricing information.

The shadow fleet

Russia – and Russian-linked groups around the world – have successfully created alternative export capacities that do not fall under the price cap. This has allowed Russia to sell oil for market prices, charging above the cap for its exports.

They have done so by setting up a ‘shadow fleet’ of vessels that do not have any links to OPC coalition jurisdictions (for example, ownership, management, flagging or insurance). As a result, the share of Russian oil transported on price cap compliant ships has fallen significantly since the OPC took effect, fundamentally eroding the policy’s leverage (see Figure 7).

The shadow fleet has allowed Russia to generate around $10 billion in extra earnings from crude oil alone since December 2022. But recent developments in response to the sanctioning of shadow tankers in different jurisdictions (see Figure 8) show that there are mechanisms to rein in the shadow fleet and increase the amount of Russian exports to which the cap applies (see Figure 7). While this might help to stem the flow of oil money to Russia, deeper implementation challenges remain.

Figure 7: Share of Russian seaborne exports on shadow tankers, %

Source: CREA

Figure 8: Sanctioned shadow fleet tankers by jurisdiction

Source: KSE Institute

Lack of reliable price information

To assess whether the price cap is complied with, authorities require information about the sales price of each shipment transported with participation of G7+ service providers. As most of the involved entities do not have access to original price information, the OPC coalition created the so-called ‘attestation system’, through which those with such information ‘attest’ to all other parties that a transaction took place in compliance with the price cap.

The problem with this approach is related to the entities that provide the attestation. As the price cap is being applied to origin-port prices (what are known as ‘free-on-board’ or FOB prices), only the (Russian) seller and the initial buyer provide the attestations. Media reporting shows that the trade of Russian oil has been almost entirely switched from global trading houses to companies in the United Arab Emirates and other places that are either subsidiaries of Russian oil companies (such as Litasco) or suspected to be linked to Russian interests. As a result, critical information needed for the price cap’s implementation stems from actors who cannot be relied on.

From the start, there has been evidence of extremely low compliance with the price cap (see Hilgenstock et al, 2023 and Wolff et al, 2023). With prices for Russian crude oil moving above the cap’s $60/bbl threshold in mid-2023, this issue (known as ‘attestation fraud’) has spread to almost all seaborne exports from Russia.

While Russian customs data are no longer available (after the end of 2023) to see the exact distribution, average export prices indicate that the issue persists (see Figure 9). Only in recent months have Russian export prices fallen under $60/bbl. In any case, this dip is not due to price cap effectiveness but rather to lower global prices.

Figure 9: Oil prices and price cap compliance

Source: Russian customs service, IEA

Next steps: fixing the price cap or targeting volumes

The price cap’s fundamental challenges pose the question of whether the system is fixable. The answer is yes, but it will not be easy, and it will require real political commitment. Simply considering lowering the price cap(s) will accomplish little if the shadow fleet is not reined in further and the issue with unreliable pricing information not addressed.

To do the former, the G7+ jurisdictions should continue to expand their vessel listings, which have proved to be quite successful. But enforcement is key. Those jurisdictions that do not impose sanctions with extraterritorial reach (that is, ‘secondary’ sanctions) must ensure that their listings lead to third-country actors’ refusal to interact with the ships and/or their cargo. This includes port authorities, financial institutions and, most importantly, the buyers of the oil.

To address attestation fraud, price information that is fundamental for the assessment of price cap compliance – and enforcement action against violators – must come from reliable sources, either ‘white-listed’ oil traders in the West or the buyers of Russian oil in China, India, Türkiye and elsewhere.

If the price cap system turns out to be beyond salvation, this leaves the only option being (partially) to remove Russian oil and natural gas from the global market. This requires threatening the aforementioned buyers of Russian fossil fuels with punitive actions should they continue their purchases. The prospect of being cut off from the US financial system is a very potent threat that has been employed in the past to extend the reach of American sanctions. Other members of the sanctions coalition – such as the EU and the UK – must develop similar tools.

While reducing the supply of Russian oil and natural gas to the global market could lead to somewhat higher prices, it would dramatically exacerbate the existing problems of the Russian economy and budget, changing the calculus of the regime (see Hilgenstock and Ribakova, 2025). If the international community is serious about putting an end to the war in Ukraine, such measures may soon be necessary. For now, what is clear is that an incomplete sanctions system is an ineffective one.

Where can I find out more?

- Why Russia’s economic model no longer delivers: Analysis by Benjamin Hilgenstock and Elina Ribakova on Bruegel.

- The Russian economy at a turning point: Report by Janis Kluge for SWP, the German Institute for International and Security Affairs.

- Russian economy on war footing: A new reality financed by commodity exports: Policy Insight paper by Yuriy Gorodnichenko, Iikka Korhonen and Elina Ribakova from the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR).

- The economics of sanctions: From theory into practice: Brookings paper by Oleg Itskhoki and Elina Ribakova.

- Russian oil exports under international sanctions: Research paper by Benjamin Hilgenstock, Elina Ribakova, Nataliia Shapoval, Tania Babina, Oleg Itskhoki and Maxim Mironov.

- Moscow’s fading shadow fleet: Russian oil revenues are more vulnerable than ever: Substack post by Craig Kennedy.

- The race to sanction Russia’s growing shadow fleet: Brookings commentary by Robin Brooks and Ben Harris.

- The impact of the 2022 oil embargo and price cap on Russian oil prices: Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas working paper by Lutz Kilian, David Rapson and Burkhard Schipper.

- Three years of invasion: EU imports of Russian fossil fuels in third year of invasion surpass financial aid sent to Ukraine: Report from the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA).

- How a bad sanctions mix saved Putin: The price of misunderstanding economics: Substack post by Luis Garicano.

Who are experts on this question?

- Robin Brooks

- Agathe Demarais

- Luis Garicano

- Yuriy Gorodnichenko

- Nigel Gould-Davies

- Sergei Guriev

- Craig Kennedy

- Lutz Kilian

- Janis Kluge

- Iikka Korhonen

- Alexandra Prokopenko

- Elina Ribakova

- Maria Shagina

- Guntram Wolff