More than two-thirds of humanity now live in countries where fertility has fallen below the level needed for a stable population. This fundamental demographic shift is transforming economies, raising questions about ageing populations, shrinking workforces and the sustainability of welfare states.

Demographic change has long been a source of concern, but the nature of that concern has shifted profoundly. In the 1960s and 1970s, fears centred on overpopulation, driven by worries that rapid population expansion would outpace the growth of food supplies and infrastructure, and deplete natural resources (Ehrlich, 1968). Today, while some economies are still experiencing pressures from high population growth, in many places, the narrative has inverted as fertility rates have been declining.

This shift reflects a fundamental change in global demographic trends. For most of human history, population growth was low and stable, averaging around 0.5% annually during the 19th century. This changed in the 20th century, when falling mortality and sustained high fertility led to a sharp acceleration, peaking at over 2% per year in the 1960s. Since then, the rate has slowed steadily. The fact that global population growth is slowing despite gains in life expectancy points to decreasing fertility rates as the dominant force behind today’s demographic decline.

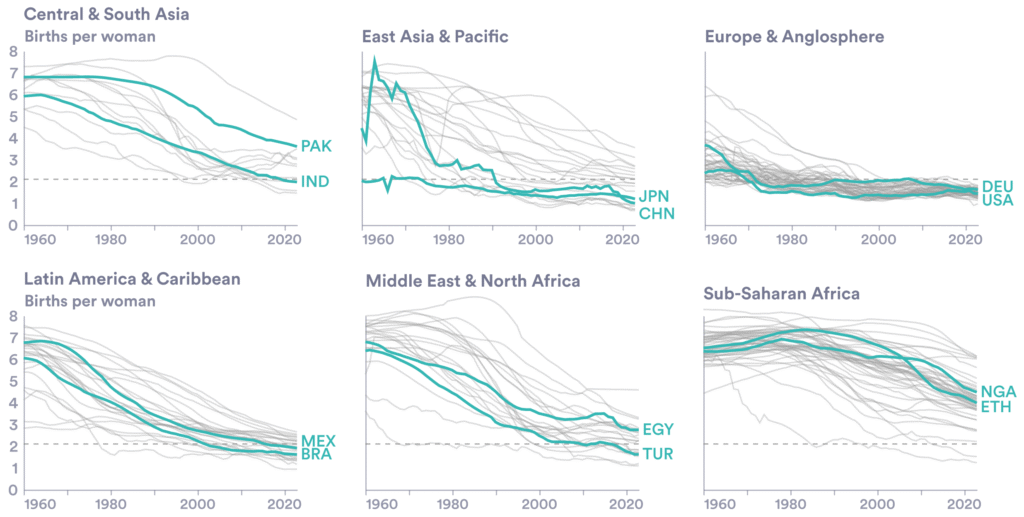

The scale of change is remarkable. Global fertility has fallen from over five births per woman in the 1960s to around 2.25 in 2023. This is only marginally above the long-run ‘replacement rate’ (the number of births per woman needed to keep population size constant) of roughly 2.1 (see Figure 1).

More than two-thirds of humanity now live in countries where fertility has dropped below this replacement threshold, and birth rates are projected to decline further. Alternative calculations suggest that the global fertility rate may have slipped even lower, implying that fertility could already be below replacement level globally (Fernández-Villaverde, 2025).

According to United Nations projections, the global population will peak at some point in the 2080s before entering a period of sustained decline. Until then, expansion will be driven largely by demographic momentum – the fact that large cohorts born when birth rates were higher are now entering their childbearing years.

Figure 1: Global fertility rates by region

Source: United Nations World Population Prospects, Human Fertility Database, and authors’ calculations.

Getting old before getting rich

One distinctive feature of today’s demographic transition is that in many economies, fertility decline is taking place at earlier stages of economic development than was historically the case. Advanced economies typically saw fertility drop below replacement levels only after becoming wealthy (EBRD, 2025; McKinsey Global Institute, 2025).

In contrast, today’s transitions are happening at lower income levels. Research also suggests that the speed of the transition is changing: more recent transitions from high- to low-fertility regimes tend to be substantially faster than in the past (Delventhal et al, 2022).

These demographic transitions open a window of opportunity known as the ‘demographic dividend’: a period in which the working-age population grows faster than the dependent population, freeing up resources previously devoted to childcare, enabling greater investment in human and physical capital, and supporting economic growth.

But today, the acceleration of demographic transitions implies that many economies will have little time before demographic ratios turn unfavourable. This means that pressures traditionally associated with rich economies (such as shrinking labour forces) will arrive in contexts that have not yet reached the levels of productivity, wealth, and fiscal and institutional capacity that could cushion the shift to an ageing society.

Should we worry about demographic decline?

One useful way to think about the economic consequences of falling fertility rates is in terms of two distinct channels: long-run effects of population on innovation and growth; and more mechanical pressures from shifting population structures (particularly the balance between working-age adults and the dependent population).

In the long run, sustained economic growth is largely driven by people discovering new ideas. More people mean more researchers; more researchers produce more innovations; and more innovations translate into higher living standards. This intuition, formalised in what economists call endogenous growth models, implies that larger populations can sustain faster technological progress by expanding the pool of potential innovators (Romer, 1990; Aghion and Howitt, 1992; Grossman and Helpman, 1991; Kremer, 1993; Jones, 2022a; Peters, 2022).

But two trends threaten this growth engine. First, as fertility falls, the potential reservoir of ideas shrinks: fewer people mean fewer minds working to solve problems and develop new technologies (Hopenhayn et al, 2022; Peters and Walsh, 2021). Second, research suggests that ideas are becoming harder to find: today, it takes more researchers to sustain the same pace of innovation as in the past (Bloom et al, 2020; Jones, 2022b).

These trends imply that living standards may eventually stagnate due to a lack of innovators coming up with new ideas. This is what has been termed the ‘empty planet scenario’ (Jones, 2022a). Global population decline could mean not just slower technological progress, but a fundamental brake on improvements in living standards over the long run.

On the other hand, slower population growth may be good for the environment, leading to lower emissions and reduced pressure on natural resources. But the timing of fertility decline suggests that these effects will materialise far too late to have a meaningful effect on near-term climate trajectories (Budolfson et al, 2025).

At the same time, a world stabilising at a lower global population is likely to exhibit lower per capita incomes than one stabilising at a higher level, reflecting the diminished pool of innovators and producers of ideas (Eden and Kuruc, 2023).

More pressing than these long-run concerns about total population are the immediate economic pressures created by shifts in population structure. When fertility declines quickly, eventually large cohorts born under higher fertility rates reach retirement age, but they are replaced by much smaller cohorts entering the labour market. As a result, the working-age share of the population falls, reducing the available labour force – and with it the economy’s productive capacity.

To understand the implications, it is useful to break down growth of GDP per capita into three components: changes in GDP per worker (productivity); changes in the employment rate; and changes in the share of the working-age population in the total population (see Figure 2).

Over the past two decades, shifts in age structures have been a less important driver of economic growth than productivity and employment across the globe. But in many regions, they still provided a meaningful tailwind. Emerging Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East and Central Asia have been benefitting from a demographic dividend that boosted their average annual GDP per capita growth between 0.34 and 0.46 percentage points.

Looking ahead, this dividend is set to fade as societies get older. In many cases it could even reverse, becoming a demographic drag on growth of GDP per capita. In the absence of significant rebounds in fertility, the working-age share would eventually stabilise at a permanently lower level, implying, all else being equal, a lower level of income per capita due to a smaller proportion of workers relative to the total population.

Figure 2: Average annual contribution to GDP per capita, 2000-23

Source: Penn World Table, World Bank and authors’ calculations.

Notes: Average annual GDP per capita growth (measured at constant national prices) is decomposed using an additive log-difference decomposition into three components: (i) changes in GDP per employed person (productivity); (ii) changes in the ratio of employed population to working-age population (employment rate); and (iii) changes in the working-age population share. Country group definitions are based on the International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook (IMF WEO) April 2025 classification.

What is the economic impact of population ageing?

Japan offers a glimpse of this future. The country's ‘lost decades’ are typically blamed on banking crises and monetary policy failures. But if you account for demographics, Japan's growth performance over the past 30 years looks remarkably similar to that of other advanced economies (Fernández-Villaverde et al, 2025). The critical difference is that the relative size of Japan's working-age population peaked in 1995 and has declined ever since, fundamentally altering the country’s demographic profile.

This shift in population structure also has profound fiscal implications. The modern welfare state channels intergenerational transfers through the tax and benefit system, collecting taxes and social contributions from some age groups while distributing cash transfers and government services to others.

The difference between what people at each age contribute to the system and what they receive follows a predictable lifecycle pattern: it is negative during childhood and old age, when people receive more than they contribute; and positive during working age, when the resulting fiscal surplus funds transfers to dependent groups.

This cycle is sustained by an implicit intergenerational contract. Each cohort supports those that precede and follow it, expecting equivalent treatment when its turn comes.

Yet the sustainability of this contract depends on a demographic equilibrium that is now shifting. Population ageing systematically alters the balance between age groups that generate fiscal surpluses and those that run deficits, placing ever-greater demands on a shrinking base of contributors. As dependency ratios increase, the arithmetic of the welfare state will become increasingly strained, meaning more debt, higher taxes or further cuts to pensions and social welfare to remain solvent.

In our own recent analysis (EBRD, 2025), we quantify the economic impact of population ageing. To isolate the effect of ageing, we compare two scenarios: in the first, the working-age population share evolves according to demographic projections; in the second, we hold this share fixed at its 2023 level, as if the age structure were frozen in the present.

The difference between these two scenarios captures the ‘cost of ageing’: the slowdown in economic growth attributable solely to the changing age structure of the population. The same exercise can be applied retrospectively to the period 2000-23, allowing us to compare how much the demographic factor subtracted from (or added to) growth in the recent past versus how much it will subtract in the future.

Figure 3: Demographic contribution to GDP per capita growth, percentage point per year, 2000-23 versus 2024-50 (projection)

Source: Authors’ calculations based on EBRD (2025).

Notes: The cost of ageing is estimated by combining United Nations demographic projections with a neoclassical growth model that incorporates demographic change; see EBRD (2025) for further details. Country group definitions are based on the IMF WEO April 2025 classification.

The results suggest a clear reversal of fortunes. Over the period 2000-23, demographics provided a sizeable tailwind in several regions, adding between 0.3 and 0.4 percentage points per year to GDP per capita growth in emerging Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and Central Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa.

Looking ahead to the period 2024-50, this boost largely disappears and often turns negative as ageing accelerates. The projected headwinds are strongest where ageing is most advanced: the demographic contribution is projected to become substantially ‘more negative’ in advanced economies (-0.46) and emerging Europe (-0.35). Sub-Saharan Africa is the main exception, where demographics continue to support growth (and even strengthen slightly), reflecting a still-rising working-age share.

How can policy-makers respond?

Against this backdrop, the question is unavoidable: what can policy-makers do to mitigate the cost of ageing? Policies that encourage more births, increased immigration and greater labour force participation are some of the most discussed options in the policy debate.

But recent analysis suggests that in many economies, none of these levers would be sufficient on their own to offset fully the negative impact of demographic decline on economic growth over the next generation (EBRD, 2025).

One fact is undeniable: the favourable demographic reality of the last century is not coming back. Like it or not, we now live in an ageing world that poses challenges that we have never faced before.

Will future generations be able to reverse the fertility decline? Perhaps. But for the current generation it is already too late, and we will have to learn to adapt to ageing societies and identify pathways to stabilise populations in the long run.

Where can I find out more?

- The demographic future of humanity: facts and consequences: keynote slides by Jesús Fernández-Villaverde, including a comprehensive visual overview of global fertility trends and their economic implications.

- The outlook for long-term economic growth: paper by Charles Jones on headwinds and tailwinds for future growth, explaining why population decline might threaten long-run living standards.

- Let's save the human species! 2026 essay by Noah Smith on why common dismissals of the fertility crisis might be misguided.

- Our World in Data – Population Growth: explore global and national data on population growth, demography, and how they are changing.

- After the Spike: Population, Progress and the Case for People: book by Dean Spears and Michael Geruso, published in 2025.

Who are the experts on this question?

- Jesús Fernández-Villaverde

- Charles (Chad) I. Jones

- David N. Weil

- Ronald Lee

- Michael Peters