Greater Manchester’s relatively high rates of Covid-19 have resulted in severe damage to the city-region’s economy. This has been compounded by heavier restrictions than elsewhere, dependence on a large commuter workforce, overcrowded housing and inadequate local government powers.

Manchester has been hit hard by the pandemic. A combination of economic and health factors specific to the city has exposed serious vulnerabilities, some of them longstanding, arising from deprivation. But the strength of the city centre and the draw of its labour market have combined with these weaknesses to make the impact of the pandemic worse.

The local economy has been hit exceptionally hard with curbs on activity, and it has an economy especially vulnerable to disruptions from the pandemic. The city has suffered from more onerous restrictions than most other cities, with a long period of ‘local lockdown’ before the tier system and then the second national lockdown were introduced. It is also more dependent on commuters than England’s other core cities, which means that the effect on the city centre of large numbers of people working from home has been more pronounced.

At the same time, worse health outcomes from before the crisis have caused higher rates of mortality, overcrowding has aided the spread and, despite the progress of devolution, the city has not had the tools it needs to fight the virus. This culminated in an ugly showdown between local and central government – highlighting the need for an empowered national and local response.

What has been the impact so far?

The full impact of the virus will not be known for some time, although we can highlight some facts. The death toll has been disproportionately high: while only one in 20 of the population of England live in Greater Manchester, one in 12 people in England who have died from Covid-19 lived here (HMG, 2020). In the second wave of the pandemic, every week since the start of October has seen over 2,000 new cases identified in the city of Manchester, and over 10,000 in the city-region of Greater Manchester.

Meanwhile, Manchester’s claimant count has more than doubled, disproportionately driven by the 16-24 year old age group, which is likely to have been a result of the shutdown of the hospitality sector. Of the working age population, 8.9% are now claiming, compared with 6.3% nationwide (Office for National Statistics, 2020).

This helps us to see that discussion of a ‘trade-off’ between the health and economic impacts of the pandemic is misguided, at least within a country where, looking across places, the two impacts will tend to be correlated. A recent report noted that ‘As well as suffering from increased mortality, the Northern Powerhouse was disproportionately hit in terms of economic outcomes (unemployment rates)’ (Northern Health Science Alliance, 2020).

Bank of England research suggests that the incidence of the virus drives a fall in consumer activity more than direct restrictions (Bank of England, 2020). Areas that experience higher levels of infection will have worse economic outcomes regardless of the restrictions regime (though this can cause added damage – see below) – and this is a story that is true across the North.

Layered on top of this, Manchester faces additional challenges that stem from its particular circumstances – making both the health and economic damage more onerous. Here we focus on two economic factors and two health factors that compound the issue.

Why has economic activity in Manchester been especially affected?

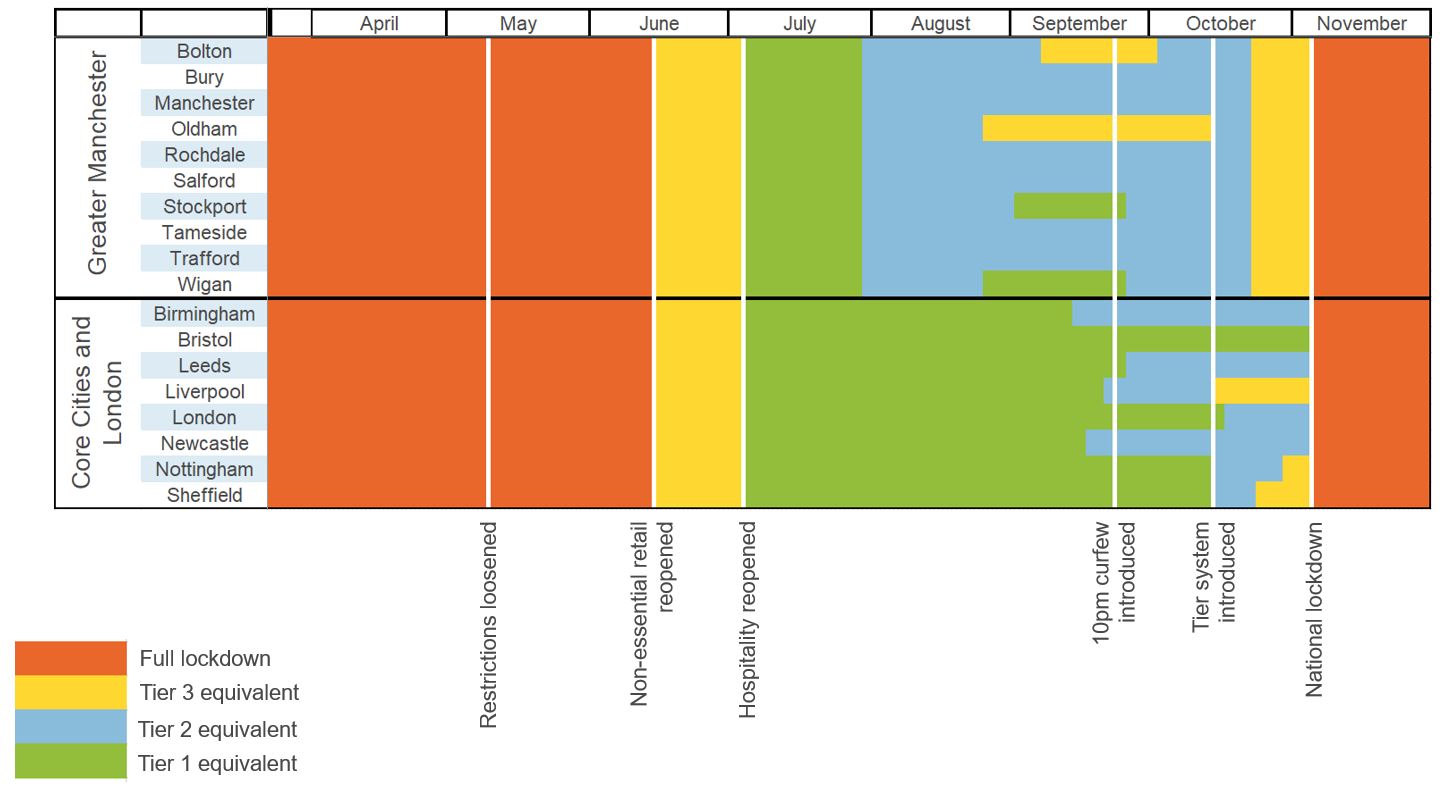

To understand how restrictions have changed across the year, we have constructed an approximate categorisation of different types of local restriction. The structure of the restrictions over the summer of 2020 became complex, with multiple local variants. We have worked backwards from the ‘three-tier’ model (which was scrapped in favour of a renewed national lockdown and has now been reintroduced) to show visually the restrictions that were in place at different times. We highlight four categories:

- Full lockdown: These are the nationally imposed restrictions that involve closure of hospitality and non-essential retail, and a ban on meeting other households (in both these respects the second lockdown has been slightly less strict than the first, with takeaways and meeting one other person outside allowed).

- Tier 3 equivalent: This includes the closure of most hospitality but non-essential retail being open. Socially it includes a ban on mixing indoors or private gardens. This was broadly the position after the second easing of the first lockdown. This level of restrictions accurately describes the situation in Bolton between 8 September and 2 October, where all hospitality closed but no social curbs were put in place, and we have also used it to describe Oldham between 26 August and 14 October, where despite hospitality staying open, all social gatherings indoors and outdoors were banned.

- Tier 2 equivalent: Here, hospitality is open, but it is severely affected by the fact that only household groups can go to a venue together, as more broadly it allows no mixing indoors. This level of restriction was introduced across Greater Manchester as part of a ‘local lockdown’ on 30 July, with the additional ban on meeting in private gardens (which had limited impact on business). With the exceptions of Stockport and Wigan, which both enjoyed a brief reprise, restrictions have only tightened since then.

- Tier 1 equivalent: This is the lowest level of restriction since the initial lockdown was introduced. No businesses are forced to close and social interaction is allowed indoors and out – initially between two households and latterly following the ‘rule of six’.

Figure 1: Restrictions across Greater Manchester and in English core cities across 2020

Source: Metro Dynamics analysis of local media. We have used local authority districts to define the boundaries of England’s core cities.

Taking a view across the whole year, Figure 1 shows that in the whole period from the start of the first lockdown until now, most of Greater Manchester has only enjoyed three and a half weeks without some form of enhanced restriction. This compares unfavourably with all of England’s core cities, which had:

- Local measures introduced towards the end of September (Birmingham, Leeds, Liverpool, Newcastle);

- Further restrictions with the introduction of the tier system (London, Nottingham, Sheffield);

- Or no extra restrictions before the second national lockdown (Bristol).

It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss whether additional restrictions were appropriate – and of course, we cannot know the counterfactual. But we should note two points:

- The restrictions failed to prevent a large spike in cases in October, with the return of students, and therefore despite causing economic damage did little to prevent a second wave.

- The frequent changing of restrictions, and the fact different regimes were in place across Greater Manchester, added to public and business confusion, and is therefore likely to have damaged public compliance and the economy.

Why has the city centre suffered?

Evidence shows that large cities are generally the parts of the country that are furthest below pre-lockdown levels of consumer spending and footfall (Centre for Cities, 2020). It seems likely that much of this is a result of workers who are no longer commuting to their offices, but following government guidance to ‘work from home, wherever possible’.

Compared with other northern areas, Manchester is especially exposed. The ‘travel to work area’ for Manchester is the second largest in England, home to 2.8 million people (see Figure 2). While not all of them will work in the city of Manchester, it is the pre-eminent employment centre, with 29.5% of all Greater Manchester’s employment based here.

Figure 2: Ten largest travel to work areas in England and Wales by population

Source: ONS Population estimates by small area. Chart by Charley Ferrari

By contrast, the northern towns of Huddersfield, Warrington and Birkenhead have seen the strongest recoveries in consumer spending across the UK.

Why has social distancing been challenging in Manchester?

Economic, social and environmental inequalities have played out in the incidence of Covid-19 infections and deaths. Who people are, where they live, what they do and their health are all important factors.

Greater Manchester already had relatively poor health outcomes. Over one in four neighbourhoods in the city-region are in the most deprived 10% nationally for health deprivation (Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government Index of Multiple Deprivation, 2019). As Figure 3 shows, among men, eight out of ten boroughs have a healthy life expectancy from birth lower than the national average (Public Health England, 2016-18).

Figure 3: Healthy life expectancy at birth (males)

Source: Public Health England . Chart by Charley Ferrari

Evidence suggests that the structure and composition of households, including overcrowding and multigenerational occupancy, is one of the key risks in making social distancing harder and keeping rates high (New Policy Institute, 2020). Overcrowded households, those with one or more rooms too few, are common in Manchester. As Figure 4 shows, 16.4% of households are overcrowded. This is the third highest outside of London and the highest in the North.

Overcrowding is often higher in more deprived areas, linked to high housing costs or multiple occupancy – where ‘common areas’ exist in a house that is shared by more than one household. In Manchester, a combination of high property prices and a young population is likely to be a contributing factor, reducing the amount of space that people can afford.

Figure 4: Percentage of households overcrowded in England’s core cities

Source: LG Inform. Chart by Charley Ferrari

Why hasn’t health devolution produced better outcomes?

Greater Manchester is one of only two mayoralties with powers over public services (the other is Greater London with responsibility for crime and health). In 2016, some health and social care powers were devolved to the city-region. The Greater Manchester Health and Social Care Partnership, made up of local government, NHS Clinical Commissioning Groups and Greater Manchester NHS Trusts and Foundation Trusts, is in charge of the £6 billion spent on health and social care, with an additional £450 million of funding to transform services.

But the types of powers given to Greater Manchester were not of the same order as those granted to the national devolved administrations of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. The city-region has been unable to mandate its own, locally appropriate restrictions, and the partnership nature of the arrangements means that there are challenges around decision-making and accountability.

As noted by the Health Devolution Commission, ‘In Greater Manchester emerging structures are not as straightforward as may be thought… contrary to what many may believe, the Mayor of Greater Manchester is not “in charge” of NHS and social care services in Greater Manchester. The decision-making body is a partnership board bringing together a wide range of leaders, including – but not exclusively – politicians.’

The pandemic is the ultimate stress test of an area’s health resilience. It may turn out that Greater Manchester’s arrangements have helped the wider system manage some of the fallout from Covid-19. But a pandemic was not envisaged when those powers were devolved or funding allocated, and they have done little to compensate for the city-region’s immediate vulnerability in the face of Covid-19. Meanwhile, national policy on lockdowns has further complicated the picture for people and businesses alike.

Compared with Greater Manchester, other city regions have even less local agency. Localised measures are unlikely to work without local control and ownership. Managing the ‘new normal’ of living with Covid-19 and economic recovery, and how the two interrelate, will require a more integrated approach, at both local and national level. This means putting public health at the heart of the next phase of devolution.

Conclusion

Greater Manchester has experienced relatively high rates of Covid-19 cases, and consequently has experienced a large economic hit. This has been compounded by heavier restrictions than other places (which have changed frequently), a dependence on a large commuter workforce, overcrowded housing, and a lack of local powers to get real traction on the issue.

Where can I find out more?

- COVID-19 and the Northern Powerhouse: tackling inequalities for UK health and productivity: Report from the Northern Health Science Alliance, which reveals a massive hit to the North’s health and economy.

- The geography of the Covid-19 crisis in England: In this report from the Institute for Fiscal Studies, Alex Davenport, Christine Farquharson, Imran Rasul, Luke Sibieta and George Stoye analyse how different dimensions of the crisis – health, jobs and families – vary across England.

- Future of cities: Report from the Centre for Cities.

Who are experts on this question?

- Mike Emmerich, Founding Director, Metro Dynamics

- Paul Swinney, Director of Policy and Research, Centre for Cities

- John Wrathmell, Director, Research and Strategy, Greater Manchester Combined Authority