Coronavirus deaths per one million people in Germany are much lower than in France, Italy, Spain and the UK. Explanations include earlier protective measures; an economy better able to accommodate remote work; a well-resourced healthcare system; and high levels of public trust in government.

Germany’s rate of fatalities from Covid-19 has been low compared with other big European countries. This is in part because the German government responded earlier with protective measures against the health threat, notably mass testing for coronavirus. The country’s comparatively successful containment of Covid-19 deaths has also benefited from favourable pre-existing conditions: an economy that is dominated by the service sectors and which can therefore accommodate remote work more widely; the high capacity and resources of the healthcare and long-term care sectors; and high public trust in government.

Background

From the end of January to 20 July 2020, Germany has had 201,823 confirmed Covid-19 cases or 2,408.85 cases per one million population. This number is lower than in the UK (4,331.41 per million) or Spain (5,566.36), and about the same as in France (2,516.27).

But what is striking about Germany is its considerably lower fatality rate. As of 20 July, the deaths caused by Covid-19 in Germany – at 108.42 per one million population – are about six times lower than those in Spain and the UK, and about four and five times lower than in France and Italy respectively (World Health Organization, 2020). These other countries may find it useful to learn from Germany's success in preventing the loss of lives from Covid-19.

This article focuses on how lessons can be drawn: first, from understanding the effectiveness of the German policies and interventions in response to the outbreak; and second, from examining the pre-existing socio-economic and healthcare system structures that enabled effective control of deaths across different settings in the country.

What does evidence reveal about the effectiveness of policies implemented to contain Covid-19 deaths in Germany?

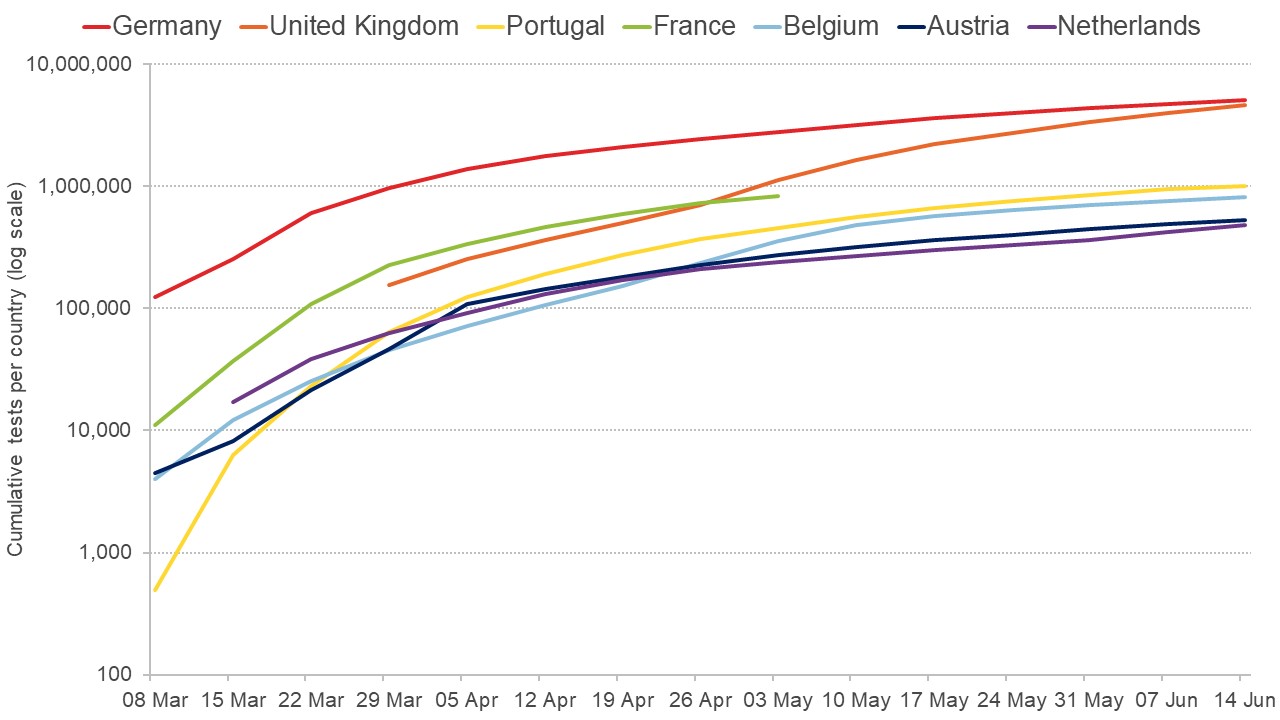

Experts concur that Germany’s mass testing policy has contributed to the country’s low fatality rate. As cases were identified early, treatment could be offered before the disease became too severe. This intense testing was made possible by the high capacity of domestic laboratories. As of 8 March, Germany had performed around 125,000 tests while France was only at about 11,000. By early April, Germany had performed more than one million tests (see Figure 1), higher than many other countries (Our World in Data, 2020).

Figure 1: Comparison of number of tests done in Germany and other countries from 1 March to 15 June

Source: Our World in Data

It is important to compare the timing of testing policies in Germany relative to other countries. Research on the experiences of 32 countries shows that the earlier that testing policies were implemented, the more effective they were in decelerating or reversing the upward trend in Covid-19 deaths (Dergiades et al, 2020).

Related question: How should we allocated limited capacity for coronavirus testing?

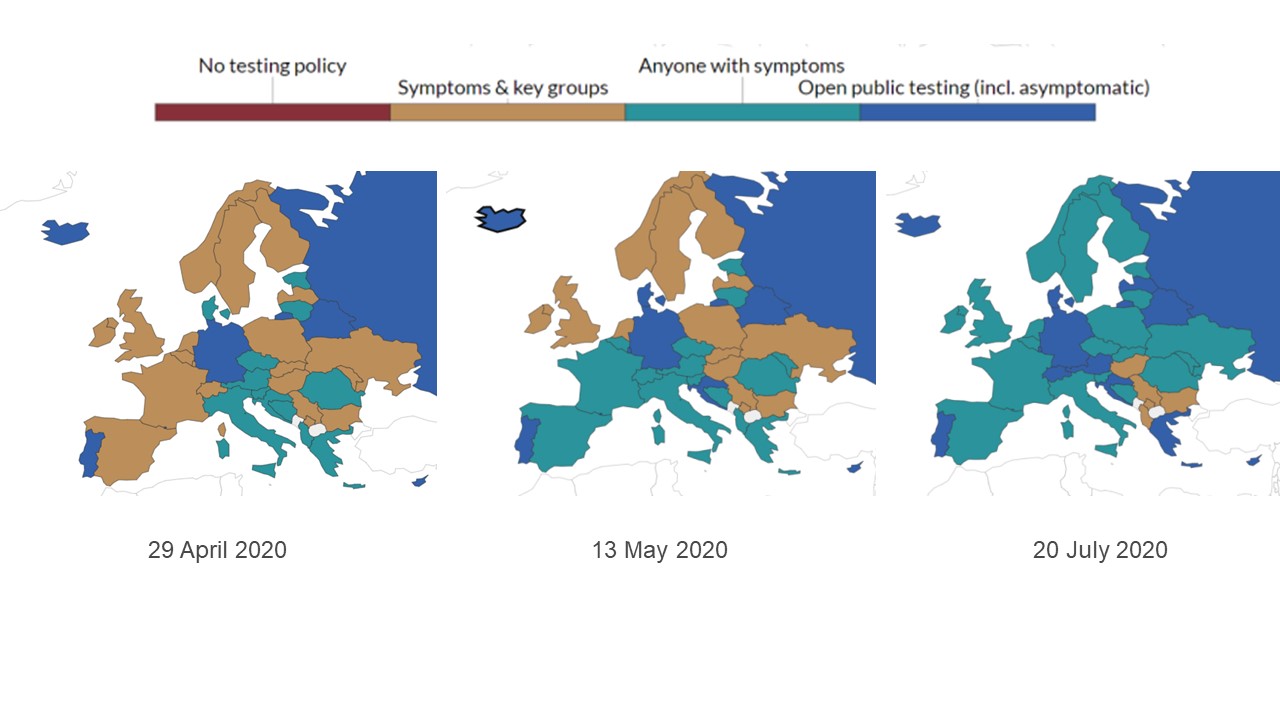

Figure 2 compares different European governments’ policies at three points in time. Since 29 April, Germany has employed open public testing, including ‘drive-through’ tests for asymptomatic individuals. In contrast, the UK, which had experienced higher fatalities at that point, had been testing only individuals from key high-risk groups presenting with symptoms. Other comparable European countries, such as France and Spain, had only been testing individuals with symptoms within the high-risk groups, and they only increased testing to other symptomatic people around the middle of May. By early July, Germany’s neighbours Denmark, Switzerland and Austria had employed an open public testing policy (Our World in Data, 2020).

Figure 2: Comparison of Covid-19 testing policies across European countries at three points in time

Source: Our World in Data (citing data from Oxford Covid-19 Government Response Tracker, Blavatnik School of Government)

In response to the Covid-19 pandemic, Germany’s health ministry provided a funding package for long-term care institutions to ensure maintenance of quality of care. To prevent Covid-19 infections in these settings where the high-risk groups reside, different federal and state-level measures were implemented, following the guidelines and recommendations issued by the Robert Koch Institut (Lorenz-Dant, 2020).

In contrast, Italy, which was heavily, hit acted late in managing the outbreak of Covid-19 in nursing homes. There was a lack of personal protective equipment for staff, no funding packages for nursing homes, pressure for individual homes to act alone in responding to the outbreak, and poor coordination between federal and regional legislators (Berloto et al, 2020).

Other effective policies enacted in Germany in response to Covid-19 include the closing of schools on 13 March, cancellation of major sports events, bans on public gatherings, and closures of restaurants, retail outlets and other non-essential businesses.

One study finds that these decisions had effectively decelerated the growth rate of new cases by half as early as one week after implementation (Hartl et al, 2020). Similarly, compliance with strict social distancing measures drastically reduced cases and fatalities, albeit at high economic costs (Quaas et al, 2020). Making the use of face masks in public places mandatory was also effective in reducing the daily growth rate of infections by 40% (Mitze et al, 2020).

How have pre-existing conditions of the German economy and healthcare sector helped the containment of Covid-19 fatality rates?

The dominance of the service sector in Germany’s economy has helped to contain fatality rates. One study finds that German regions in which the industrial structure enables a larger share of jobs to be performed from home have experienced significantly fewer Covid-19 cases and deaths (Fardinger and Schymik, 2020).

The implication of regional differences in the economic structure of Germany is also seen in the recent increase in the Covid-19 infection rate after protective measures were eased. By late June, there were several local outbreaks in regions with meat processing plants and logistics companies (Robert Koch Institut, 2020).

The decentralised nature of Germany’s government has also played an important role. It allows states to adapt national guidelines to local needs, as well as fostering competence and quality of service provision in local healthcare, which in turn ensures public trust in the system’s capacity (Weiss, 2020).

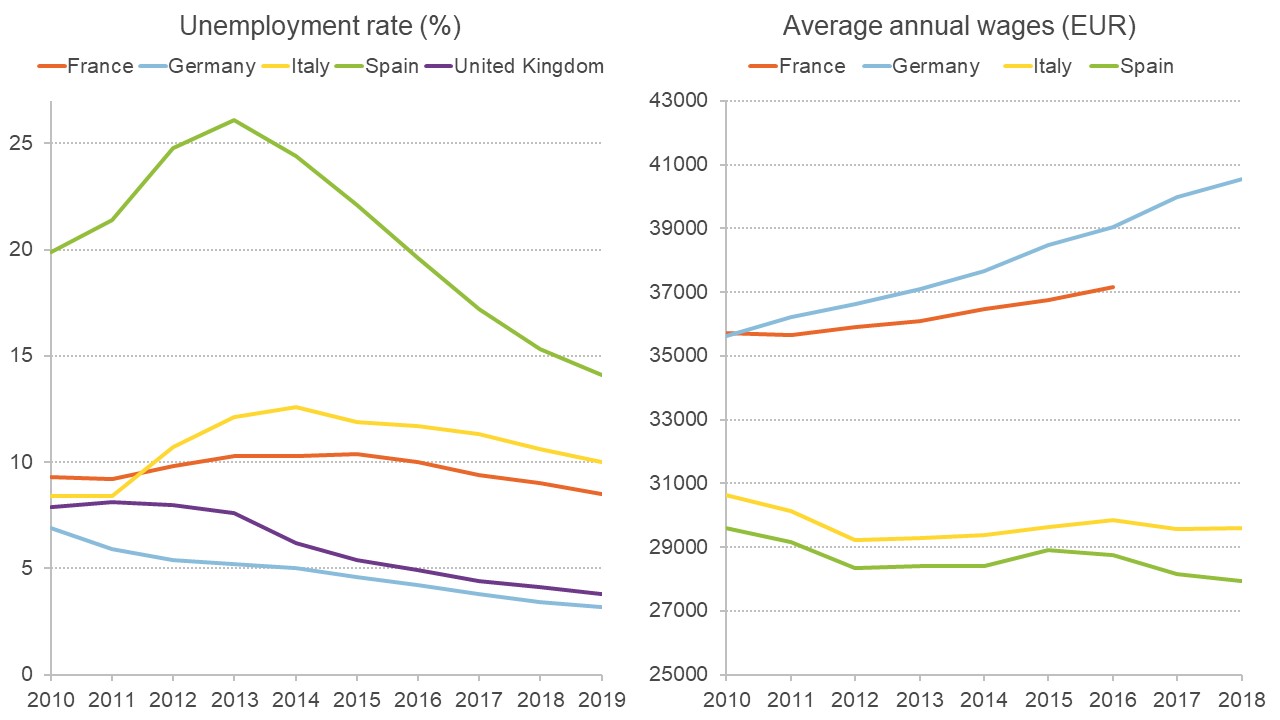

Germany’s solid economy is another key pre-existing condition that has enabled the low fatality rate. For example, there was a decrease in the unemployment rate and a positive trend in annual average wages over the last decade, as Figure 3 shows.

These trends boosted the resources for Germany’s system of social health Insurance, which is mainly financed through mandatory income-related contributions (OECD, 2019). Thanks to this, Germany’s sickness fund had an accumulated financial reserve of over €21 billion in 2018, more than quadruple the minimum reserve amount required (Federal Ministry of Health, 2019).

Germany also has the highest per capita healthcare expenditure in the European Union (EU), spending 11.1% of gross GDP on health, compared with the EU average of 9.9% (BBC, 2020). As a result, this economic framework has been a direct channel for deploying resources strategically, aimed at maintaining a low fatality rate during the crisis.

Figure 3: Comparison of unemployment rate trend and average annual wages in Germany and other countries (2010 to 2019)

Sources: International Monetary Fund and Statista

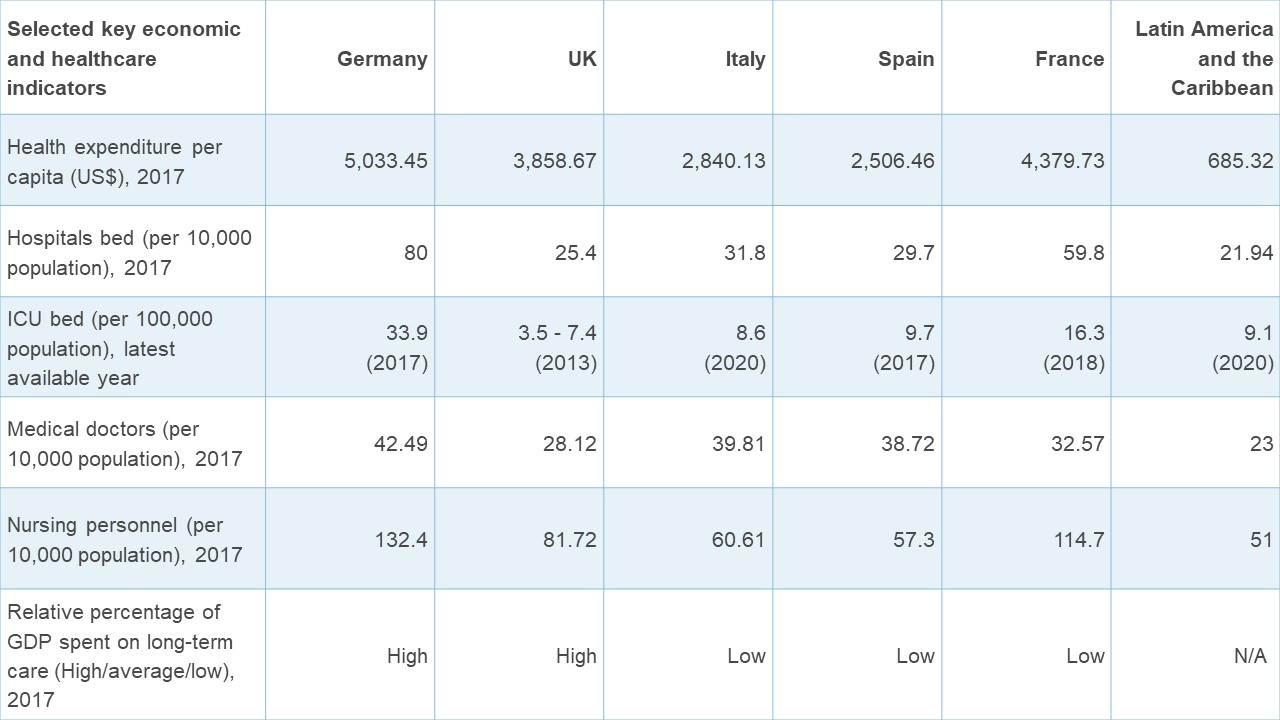

Given the availability of healthcare resources, Germany has had higher health expenditure per capita during the crisis, as well as more intensive care beds and more healthcare workers per capita, than France, Italy, Spain, the UK, and the Latin America and the Caribbean average (see Table 1).

In addition, the number of laboratories allocated for Covid-19 testing is significantly higher in Germany: around 300 since February (LABMATE, 2020), while Public Health England centralised testing in the eight labs that it controlled in mid-March (Buranyi, 2020).

As mentioned, Germany’s testing capacity was crucial in containing infection and fatality rates. This testing capacity advantage was unique to Germany, where laboratories began developing a test kit for the new virus in mid-January, with the first one developed at Berlin's Charité hospital. The country was therefore able to stockpile a large number for domestic use before manufacturing more to meet worldwide demand (von Graevenitz, 2020).

Germany has also had limited infection transmission in long-term care facilities. This may be explained by the high public expenditure on long-term care in Germany (€464.9 per capita), considerably higher than in France and the UK with €374.3 and €355 in 2015, respectively (European Commission, 2019).

Table 1: Comparison of key economic and healthcare indicators in Germany and other countries from 2017 to nearest year.

Sources: World Bank; the World Health Organization; Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development; Incisive Health; Prin and Wunsch, 2013.

Another relevant dimension is the high level of trust of the German population in their government in times of crisis. Trust in government had increased over the period from 2007 to 2012 (OECD, 2013), and a survey in May in the Covid-19 context revealed that Germans’ trust in federal and state governments comes first before other institutions such as businesses, the media and NGOs (Schildt, 2020).

Since the Covid-19 outbreak, Chancellor Merkel’s leadership has enjoyed strong public support (as well as little political opposition) for being seen as scientifically informed, rational and level-headed throughout the crisis (Dempsey, 2020). A survey reflects this confidence in the government: only 20% of Germans believe that the spread of the virus was due to the authorities being unable to enforce preventative countermeasures – considerably lower than in France and the UK at 37% and 31%, respectively (Ipsos, 2020).

In addition, the German population’s behavioural patterns may be an outcome of self-regulation and the ability to forgo instant gratification (Deutsche Bank, 2020), potentially supporting compliance with public health measures to control the spread of the virus. But it is worth noting that protests and vocal dissatisfaction have occurred recently, mainly due to the enforcement of strict lockdowns associated with localised outbreaks in regions that rely heavily on the meat processing industry (Reuters, 2020).

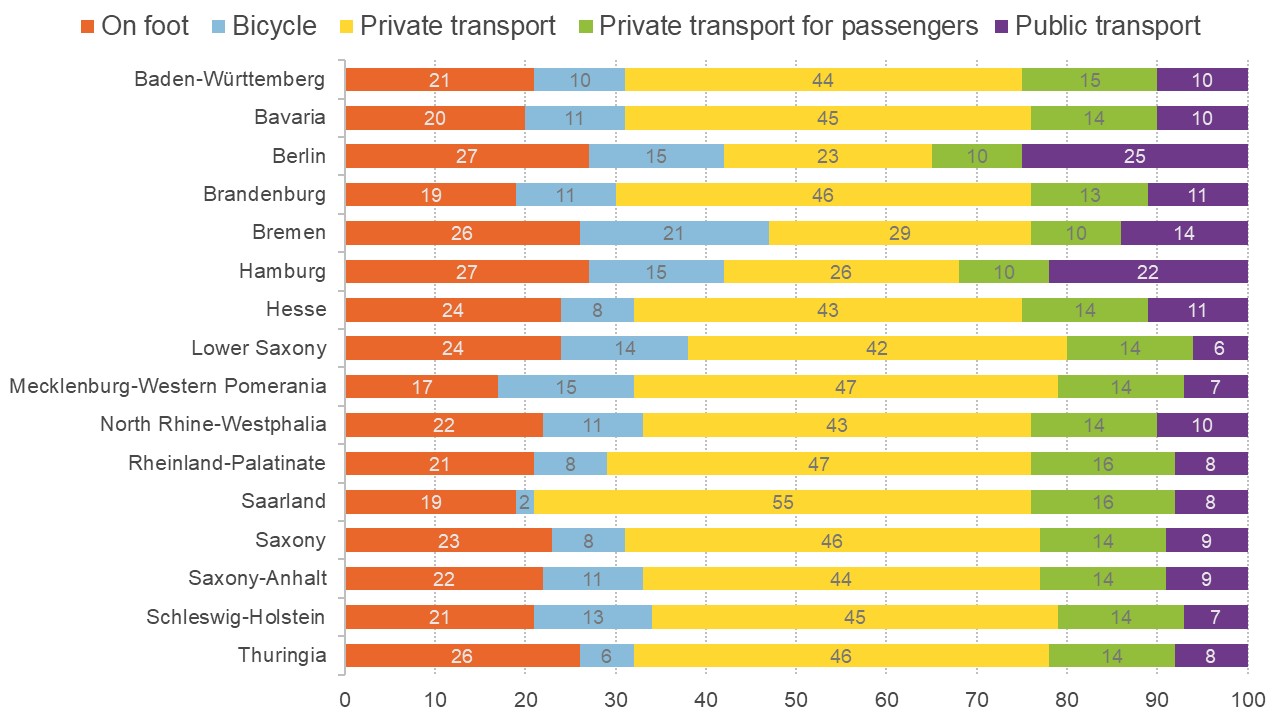

Use of public transport might also be a relevant factor in the spread of Covid-19, given the close and frequent contacts between passengers. Figure 4 shows that public transport is not the main means of transport across all German states except Berlin and Hamburg. More than 70% of journeys are made in private transport, on foot or by bicycle (Die Verkehrsunternehmen, 2017). Germans seem to travel more in private cars, as the country’s share of land transport passenger-kilometres travelled by passenger car is higher than in Spain, Italy and France (Statista, 2020).

These patterns of high reliance on private vehicles relative to public transport may have contributed to containment of the virus, although there is no substantive evidence that links relatively low public transport use with low fatality rates in Germany. Nevertheless, in the US context, one study reveals that African-Americans may be dying from Covid-19 at a higher rate than white Americans in part because of their greater reliance on public transport for commuting (Harrison, 2020).

Figure 4: The main means of transport by states in Germany in 2017

Source: Die Verkehrsunternehmen

What information is needed for better decision-making or policy-making in the future?

Using the case fatality rate is relevant here as it reflects deaths specifically from Covid-19. Given Germany’s mass testing capacity, we can be relatively assured about the reliability of the country’s data on the number of confirmed cases and related deaths (Our World in Data, 2020; Hartl et al, 2020). Nevertheless, the case fatality rate may underestimate total deaths.

The case fatality rate shows the number of people who have tested positive that we can be sure to have died because of the virus. This is different from the infection fatality rate, which is the actual proportion of people who die after being infected. The latter is extremely difficult to measure accurately and it will vary across countries, depending on testing policies and patients with conditions that complicate attribution of the cause of death (Henriques, 2020).

Given rising concerns about the disproportionately large effect of Covid-19 on ethnic minorities and the underlying problem of health inequalities, national surveillance agencies should collect and analyse data on the breakdown of infection and deaths by ethnicity. Currently, Germany and many other European countries, aside from the UK, do not yet assess data on Covid-19 by ethnic group (Pan et al, 2020).

In the near future, it will be important to conduct a systematic investigation of different countries’ responses to the Covid-19 crisis and their associated outcomes across health and socio-economic indicators. It will also be desirable to examine the extent to which Germany and other countries followed WHO directives and the association with their comparative effectiveness in managing the crisis. These assessments will help to inform future policy-making and promote the resilience and efficiency of healthcare systems in managing a crisis of this magnitude.

Where can I find out more?

The Robert Koch Institut in Berlin is the main source of research and information that the German government and public relied on with regards to the country’s Covid-19 development.

Covid Economics, Vetted and Real-Time Papers: a series of online publications from the Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Cambridge Core blog on Germany’s response to the coronavirus pandemic, providing updates on federal and state-level measures and related those assessments of implemented policy measures.

Germany’s NDR podcast covers the current research track, new insights about the infection and the course of the disease.

German Council of Economic Experts

Who are experts on this question?

- Christian Drosten

- Jeremy Rossman

- Marcel Fratzscher