The effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on the economy will depend on many factors, one of which is who can work from home and what impact that has on their productivity. Ability to work from home varies by occupation, income, age, gender, ethnicity and location.

Productivity – usually defined as output per worker – is the key driver of long-term economic growth and higher standards of living. How it is affected by the Covid-19 pandemic – and, in particular, by the lockdown – will depend on many factors, one of which is who can work from home and what impact that has on their output. This will become more important the longer there is a need for social distancing to avoid spreading infection.

What does evidence from economic research tell us?

- Higher-income workers are more likely to be in jobs that can be done from home.

- Workers in London are more likely to be in jobs that can be done from home.

- Working from home has been more prevalent in sectors such as finance, insurance, professional and scientific, and information and communications.

- Women are more likely to be in a job that can be done from home.

- Women are more likely to have increased childcare and other homework duties, which reduces their productivity when working from home.

- The workers who are least likely to be able to work at home are the young, the less educated and ethnic minorities (Bell and Blanchflower, 2020).

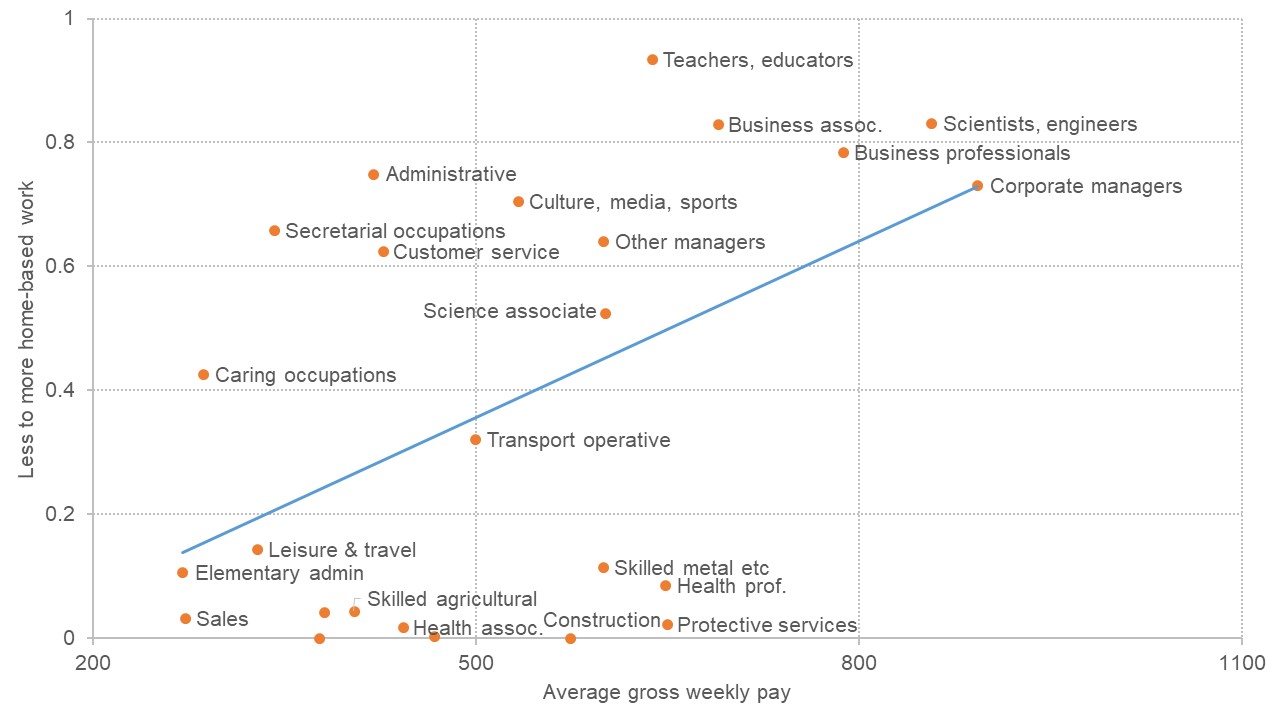

Figure 1 shows which occupations might be able to work from home against average weekly earnings in that occupation. The measure of whether a worker can work from home is based on the tasks that people in that occupation typically have to perform.

For example, if a job requires workers to use specialised machinery, to be in close contact with customers (for example, haircuts) or to work outside (for example, construction), then it will not be amenable to home-working. On the other hand, many desk-based occupations such as legal work, management and computer programming (shown towards the top of the graph) can fairly easily be done from home.

One problem with this approach to classifying occupations is that it is based on pre-crisis information on the tasks that are required in a job. These could change in response to the crisis: for example, many GPs are now seeing patients online, something that they did not happen before the crisis.

Figure 1 shows how the ability to work from home correlates with average incomes in the occupation. Workers in lower-paid jobs are less likely to be able to work from home.

Figure 1. Amenability of different occupations to home-based work against average earnings for different occupations

Source: Costa Dias, Farquharson, Griffith, Joyce and Levell (2020) ‘Getting people back into work’

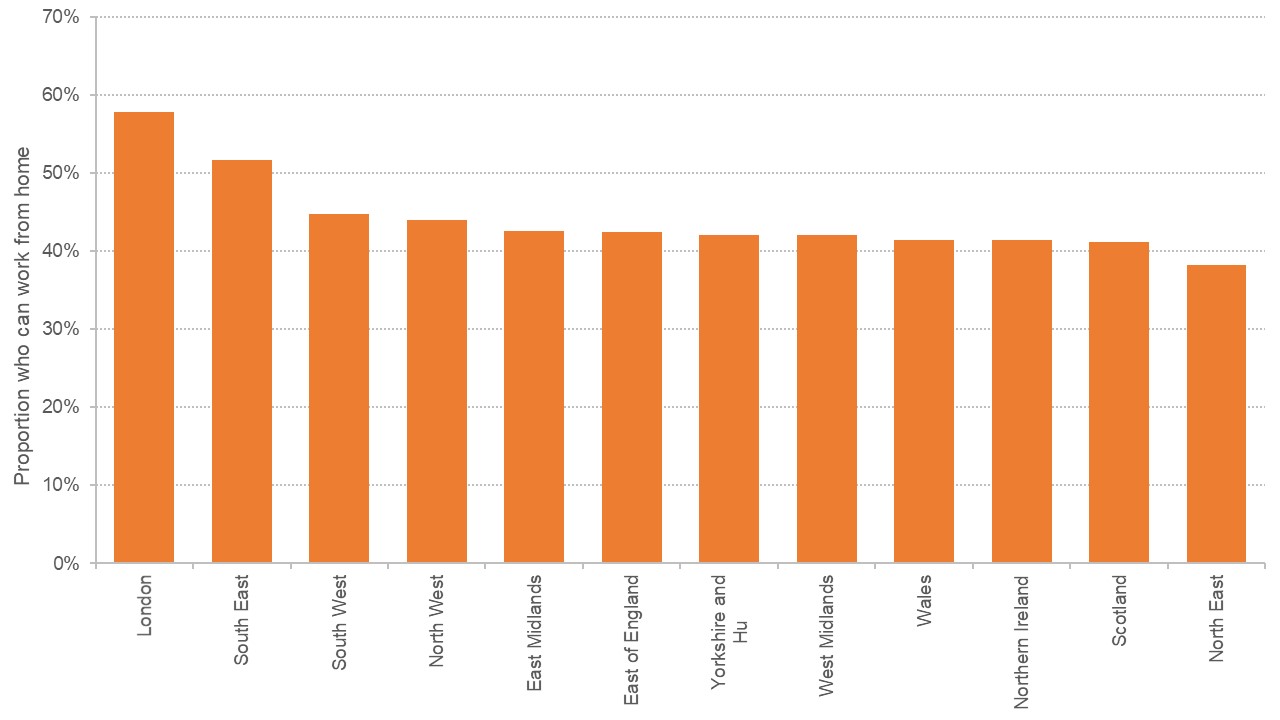

Figure 2 shows how ability to work from home varies across region. The occupations of workers in London are on average considerably more amenable to home-working than those in the rest of the country. For example, 58% of workers in London are in occupations amenable to home-working compared with 38% in the North East of England (see Magrini, 2020 for more details).

Figure 2. Share of workers in occupations that could be done at home by region

Source: Authors’ calculations using Quarterly Labour Force Survey 2019 and measures of whether occupations can be worked from home taken from Dingel and Neiman (2020). Calculations based on region of residence.

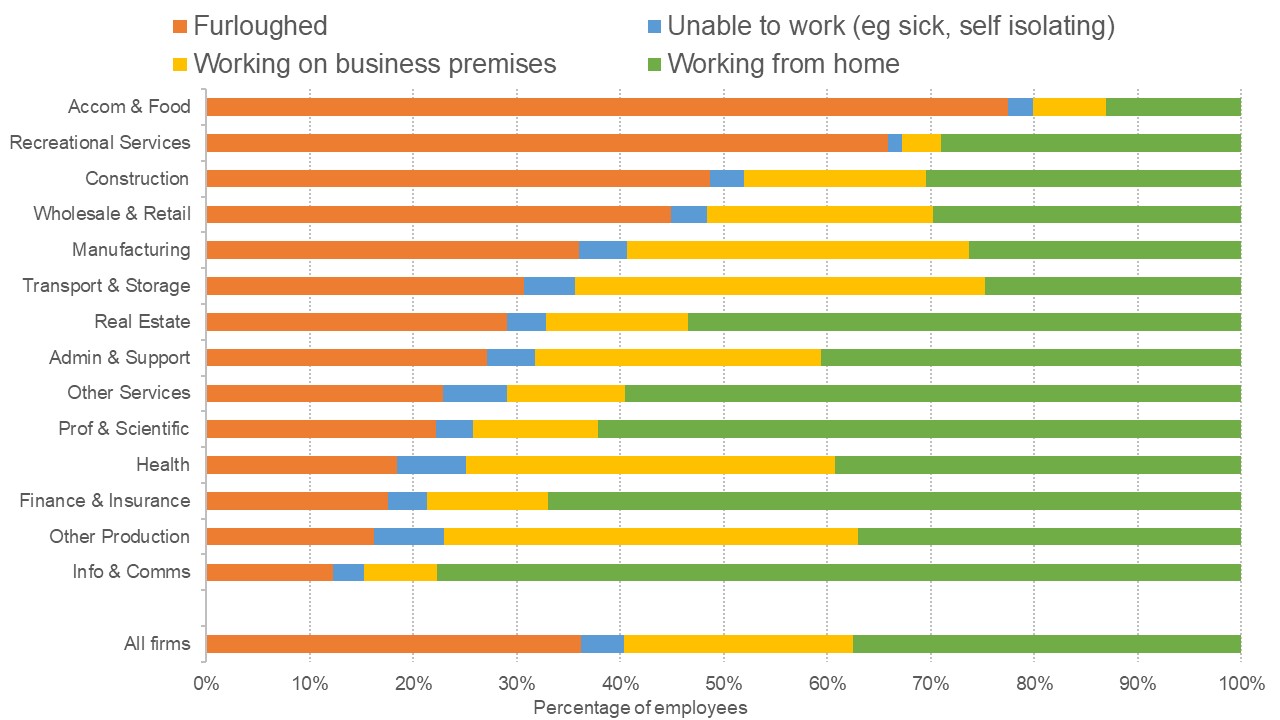

Data from the Decision Maker Panel, a monthly survey of UK firms, reports actual numbers of people working from home. Figure 3 is for April 2020. Working from home has been more prevalent in sectors such as finance, insurance, professional and scientific, and information and communications.

Figure 3: Which workers are working from home, April 2020

Source: Decision Maker Panel survey

Note: The results are based on the question ‘Approximately what percentage of your employees fall into the following categories as of April 2020?’ Respondents could assign their employees to the following categories: (i) Still employed but not required to work any hours (e.g. ‘on furlough’), (ii) Unable to work (e.g. due to sickness, self-isolation, childcare etc.), (iii) Continuing to work on business premises’.

What is the likely impact on productivity?

The jobs that can be most easily done from home are mainly in higher productivity service industries. It is too early to say whether this pattern of working will persist in the UK, and whether it will improve or reduce productivity. Evidence from China suggests that at least in some settings, working from home can improve productivity (Bloom, 2015).

But there are several factors that may hamper productivity:

- First, the presence of children (not only in terms of caring responsibilities while schools remain shut, but also having to act as teachers, which could detract from work time).

- Second, not having an optimal space in which to work. Not everyone has an office at home where they can go to work; many people may be working in a shared common space.

- Third, people are not working from home out of choice (it has been enforced) and this may impinge on wellbeing and motivation.

- Finally, social interaction is arguably necessary for creativity and innovation. Video conferencing may not be a perfect substitute, for example, due to family interruptions.

Working from home may become more commonplace in some businesses and industries where it has turned out to be easy to work effectively during the lockdown, and not adversely affected productivity.

But preliminary evidence shows that there may be important differences in the impacts on productivity between men and women. For example, mothers report taking on more of the burden of childcare than fathers (Adams-Prassl et al, 2020).

Where can I find out more?

When face-to-face interactions become an occupational hazard: jobs in the time of COVID-19: Researchers Besart Avdiu and Gaurav Nayyar at Brookings Institute in the US discuss which jobs can be done at home and which require face-to-face interaction.

Inequality in the impact of the coronavirus shock: Researchers at Cambridge and Oxford universities team up and report on new survey evidence for the UK.

US and UK labour markets before and during the COVID-19 crash: David Bell and Danny Blanchflower discuss how the labour market has changed over the crisis.

Getting people back into work: Researchers at IFS discuss some key economic issues that the UK government needs to face when thinking about how best to get people back into work.

Read about the joint initiative by the Bank of England, Stanford and University of Nottingham to collect data directly from business on expectations and uncertainty in the Decision Maker Panel.

The costs and benefits of home office during the Covid-19 pandemic: evidence from infections and an input-output model for Germany: Harald Fadinger and Jan Schymik discuss the impact of working from home in Germany.

COVID-19 and gender gaps: latest evidence and lessons from the UK: Claudia Hupkau and Barbara Petrongolo discuss the impact of the crisis on women's labour market prospects.

Business disruptions from social distancing: Miklos Koren and Rita Peto provide new evidence of the reliance of US businesses on human interaction.

How will Coronavirus affect jobs in different parts of the country?: Elena Magrini writing for the Centre for Cities.

Who are UK experts on this question?

- David Bell, University of Stirling

- Rob Joyce, IFS

- Barbara Petrongolo, Queen Mary

- John Van Reenen, London School of Economics