The UK labour market seems to have bounced back to pre-pandemic levels. But new data reveal that part-time work has dropped significantly, while the number of claimants of unemployment benefits remains higher than two years ago. There are also different rates of recovery across regions.

Yesterday saw the release of new labour market data for the UK. This update summarises some of the key elements.

On a number of the headline measures of labour market activity – principally the unemployment rate – the UK and its constituent regions and nations seem to be back where they were before the pandemic.

Further, vacancy data suggest that demand for workers remains robust.

Figure 1: Vacancies

Source: Office for National Statistics (ONS)

But looking a little closer shows that there are some important differences from the pre-pandemic labour market.

First, it is important to note that despite the employment rate sitting at 75.5% – not far off pre-pandemic levels – hours worked remain over 3% lower than two years ago.

Figure 2: Hours worked

Source: ONS

One aspect of this has been the drop in the number of people working part-time through the Covid-19 crisis, which remains significantly below pre-pandemic levels. There are now around 460,000 fewer people working part-time than there were two years ago. By comparison, full-time employment is up by just over 33,000.

Figure 3: Part-time working

Source: ONS

Payroll employment data from HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) give us a new, and higher frequency (monthly), measure of employment patterns.

While there are a record number of people registered for PAYE in the UK, these data expose regional differences in economic recovery across the UK. For example, the data for North Eastern Scotland show the effect of the continued challenges caused by a combination of the pandemic and the downturn in the oil and gas sector. Meanwhile, payroll employment in Cornwall and the Scilly Isles has strongly rebounded since last summer.

Figure 4: Payroll employment

Source: HMRC and ONS

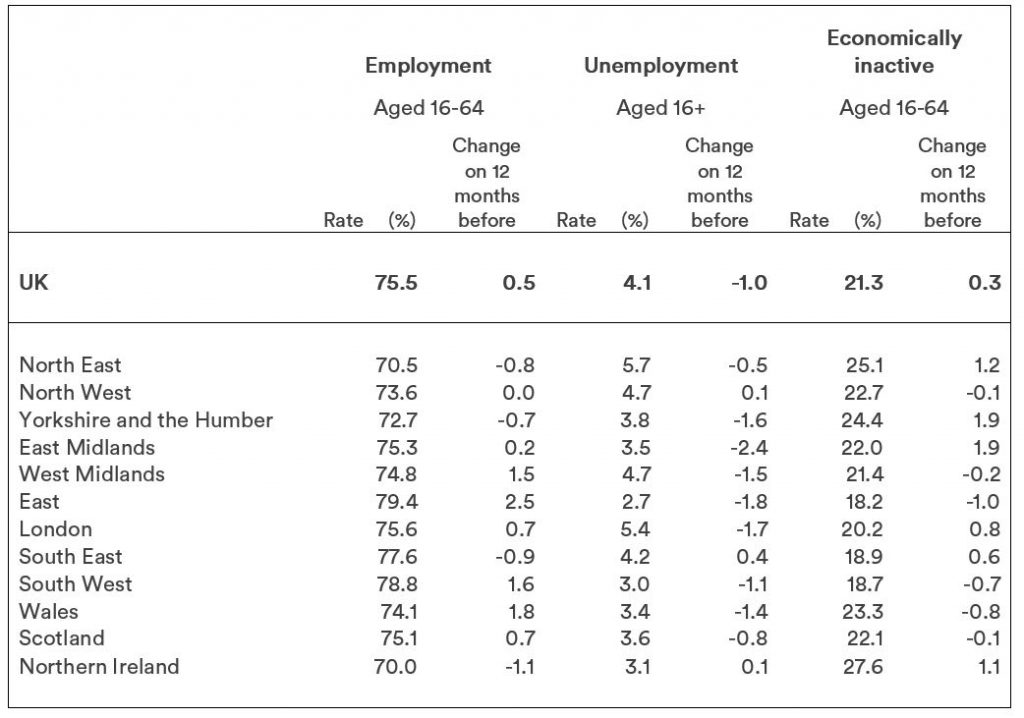

Other regional indicators are presented below.

Table 1: Headline regional labour market indicators

Source: ONS

Unemployment

The unemployment rate across the UK is currently 4.1%, which is more or less where it was two years ago. But the number of people claiming unemployment-related benefits remains over 52% higher than pre-pandemic. This translates to an additional 641,000 people.

It has long been understood that not everyone who is unemployed accesses unemployment-related benefits. This is one reason why the unemployment rate has tended to be higher than the claimant count.

But the pandemic has exposed another key difference between these figures: not everyone who claims unemployment-related benefits classifies themselves as unemployed in the Labour Force Survey.

There are a couple for reasons for this. First, they may be in work but on low hours and/or income and accessing support through Universal Credit. Second, they may be temporarily inactive and therefore not actively looking for work.

Figure 5: Claimant count

Source: ONS

Economic inactivity

Finally, while there was real concern about economic inactivity among younger people in the early stages of the pandemic, this has dropped back significantly. But throughout the Covid-19 crisis we have also seen a continued increase in the number of people aged 50-64 who are economically inactive.

Worryingly, the main explanations for this seems to be sickness (either temporarily or long term) and ‘other’ reasons. Other here is defined by the Office for National Statistics as including: those who are waiting for the results of a job application; have not yet started looking for work; do not need or want employment; have given an uncategorised reason for being economically inactive; or have not given a reason for being economically inactive.

Figure 6: Economic inactivity

Source: ONS

Conclusions

Headline indicators, such as the UK's employment rate, present a labour market that is largely back to where it was before the pandemic. But these miss the important changes set out in this article, not least variations across workers of different ages, and across different local economies.

The longer-term impact of the pandemic on the UK labour market, reshaping how we work – how much we work – and who works, are far from clear. But there are some worrying patterns emerging, most notably around the enduring health effects of the pandemic on the labour market.

Where can I find out more?

- Labour market overview: January 2022, Office for National Statistics.

- Coronavirus and the effect on labour market statistics: This report by the Office for National Statistics looks at the effect of lockdown on collation of labour market information.