Scotland may soon have a second referendum on whether to remain part of the UK. Economic issues will be a key part of the debate – from the fiscal policy institutions needed for an independent country to choice of currency and the future relationship with the European Union.

Scotland’s first minister has announced the intention to hold a second Scottish independence referendum by the end of 2023. This would be a little less than a decade since the 2014 referendum, in which nearly 45% of voters were in favour of Scotland becoming an independent country and just over 55% were against. The UK government has, so far, rejected calls for a second referendum.

Economic issues continue to be at the forefront of arguments for and against Scottish independence. What economic theory and data can be used to help us to understand the issues at the heart of this debate? What do they tell us about the opportunities and challenges of independence for both Scotland and the rest of the UK? And what is left unknown?

Scotland’s constitutional debate

In 2014, the people of Scotland voted 55% to 45% in favour of remaining part of the UK. Turnout was remarkably high at nearly 85% of the electorate, which for the first time included 16 and 17 year olds. Since then, voters in Scotland have remained energised about the constitutional debate.

Figure 1: Map showing the 'yes' voter share in the 2014 referendum

Source: BBC

A key argument made by the pro-Union side during the 2014 referendum campaign was that independence would lead to Scotland exiting the European Union (EU). This is why, following Brexit, debates about a second independence referendum gained a new edge, particularly as the Scottish electorate voted in favour of remaining in the EU by a margin of 62% to 38%.

The Scottish government argues that the UK’s decision to leave the EU represented a ‘material change in circumstance’ that justifies a second referendum. In contrast, the UK government argues that the 2014 vote settled Scotland’s constitutional status for at least a generation.

The latest opinion polling continues to show that the country remains relatively evenly split on the question of Scotland’s constitutional status.

Figure 2: Independence referendum vote intention

Source: What Scotland thinks

Note: Based on polls that asked how people would vote in response to the question, ‘Should Scotland be an independent country?’ Those saying ‘don’t know’ or ‘would not vote’ excluded.

Debates about if and when a second referendum might take place are likely to rumble on, as will the political arguments for and against independence.

Against this backdrop, we thought that it would be useful to help to inform the debate by asking leading experts to look at what the evidence tells us – and crucially doesn’t tell us – about important economic issues that lie at the heart of the discussion on Scottish independence. In a series of articles over the next few weeks, economists from across the UK, and further afield, will be providing short reviews of some of these key issues.

Our purpose is not to argue for or against independence (or indeed for or against a second independence referendum), but simply to help people become more informed about the core arguments and to highlight sources of information and data that – if you are interested – you can use to find out more about these issues for yourself.

What are the key areas of debate?

One of the challenges in attempting to bring economic evidence to bear on questions around Scottish independence is that there are few historical precedents to which we can turn for lessons. That being said, in this series we will be looking at some other experiences, including Ireland (Eoin McLaughlin and Sean Kenny from University College Cork) and the Czech Republic/Slovakia (Jan Fidrmuc, Université de Lille and Jarko Fidrmuc, Zeppelin Universität) to see what insights – with appropriate caveats – emerge from their experiences.

More generally, this means that when discussing Scottish independence, we need to be clear about the uncertainties that exist when trying to predict what might happen. The need for detailed negotiations to establish an independent Scotland and its terms of ‘exit’ from the UK on all manner of issues, including the division of all assets and liabilities, only adds to the uncertainties.

As we will see throughout the series, there are also important gaps in our economic data and statistics. If there is one conclusion that we hope people will take from these articles therefore, it is that any bold claims – by either side of the debate – that assert exactly what will happen after Scottish independence need to be taken with a pinch of salt. Issues of uncertainty (good and bad) and how they might affect businesses will be a source of discussion in an article by Brad MacKay (University of St Andrews).

What are the key issues on which economics can help to inform the debate?

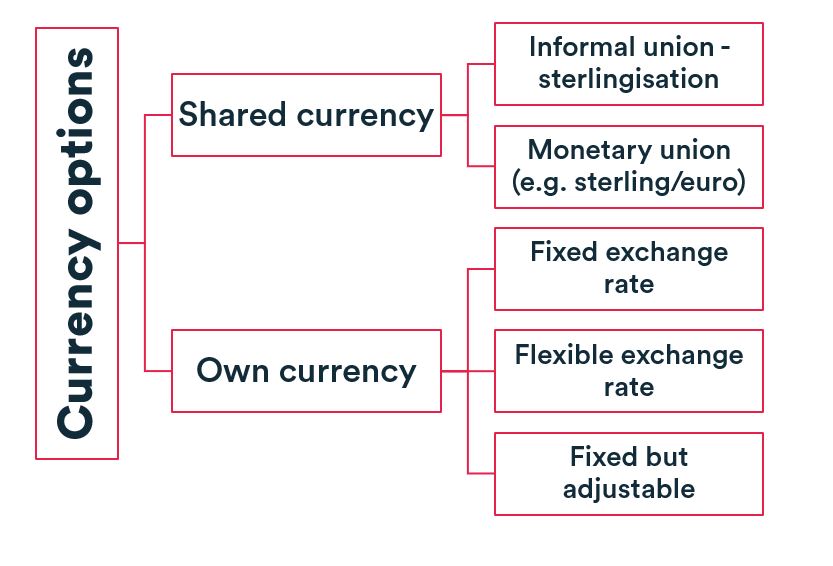

One of the most controversial areas is that of currency. The currency choice of a country reflects much more than simply the type of bank notes and coins in your pocket. Instead, it underpins all aspects of macroeconomic policy and financial stability in an economy.

Like all other parts of the UK, Scotland currently uses sterling, with monetary policy set by the Bank of England. If Scotland were to become independent, it would need to decide on its future currency and monetary system. This may include establishing its own currency, central bank and financial regulation arrangements or sharing another currency with key partners (for a detailed discussion of options – in the context of the 2014 referendum – see Armstrong and Ebell, 2014).

Figure 3: Currency options

In 2014, the Scottish government’s position was to enter a formal currency union with the UK, with the Bank of England acting as the central bank for a ‘sterling zone’. But in advance of the referendum, the UK government said that it would not agree to such an arrangement in the event of Scottish independence.

The current position of the Scottish National Party (SNP) – the current party of government and by some distance the largest pro-independence political party in Scotland – is that it will seek to use sterling post-independence with or without a currency union. Without a formal agreement this would be akin to dollarisation (which is known in Scotland as ‘sterlingisation’). Such a model has not been tried in a country with such a high income as Scotland and has typically been the chosen regime in countries like Panama. John Kay has recently spoken on this option in a public lecture at the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

Other options are available, ranging from establishing a new Scottish currency that could either ‘float’ (with the exchange rate determined by market supply and demand, as is the case with the pound today) or be ‘fixed’ (to the pound, to a basket of currencies or to another currency such as the dollar or euro). A fixed exchange rate could be ‘managed’ allowing some flexibility at the margins.

Macroeconomists will debate the strengths and weaknesses of each arrangement, but a particularly tricky issue to navigate is how to make the transition from one steady state to another. Ronald MacDonald (University of Glasgow) and Iain Hardie (University of Edinburgh) will discuss some of these issues in their articles on the currency choices facing an independent Scotland.

Another issue is fiscal sustainability. As part of the UK, Scotland does not run a separate system of public finances. The Scottish government has its own budget, but it must balance that every year (albeit with some modest borrowing powers). Running a sustainable fiscal position will be important for a newly independent Scotland.

There is much debate about what Scotland’s fiscal deficit might look like under independence. This reaches a crescendo each year on the day of publication of the Scottish government’s Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland (GERS) report.

Away from the controversy, what do we know about the position of Scotland’s public finances? (A useful summary is provided in Roy and Spowage, 2021). Scotland currently has higher public spending per head than the UK as a whole. This is largely driven by the Barnett formula, which has locked in higher relative spending in areas such as health and education in Scotland, but also reflects a slightly larger take-up of social security payments.

Figure 4: Identifiable public spending per head by devolved nation and English region (2019/20); UK average = 100

Source: HM Treasury

At the same time, onshore tax receipts per head are slightly lower than in the UK as a whole (by approximately £380 per head in 2020/21). The result is a larger estimated fiscal deficit vis-à-vis the UK (-8.8% versus -2.6% in 2019/20, and -22.4% versus -14.2% in 2020/21 at the height of the pandemic). David Phillips (Institute for Fiscal Studies) will discuss this further in an article on the core fiscal issues for an independent Scotland.

A third key consideration is around economic borders. The rest of the UK is Scotland’s largest trading partner, while an independent Scotland would of course become an important trading partner for the UK. In 2019, around 60% of Scottish exports were to the rest of the UK. This compares with 19% of total exports destined for the EU.

Table 1: Scotland’s exports

| Export destination | Value of exports (2019) | Growth since 2010 | Share of total exports (International and the rest of the UK) |

| International | £35.1 billion | 43.0% | 40.2% |

| ….of which EU | £16.4 billion | 49.6% | 18.8% |

| …..of which non-EU | £18.7 billion | 37.8% | 21.4% |

| Rest of the UK | £52.0 billion | 15.3% | 59.8% |

Source: Export Statistics Scotland

Like the rest of the UK, Scotland has now left the EU’s single market and lies outside the EU’s customs union. Should an independent Scotland seek to rejoin the EU’s single market and/or customs union, then it would have to contemplate an economic border between Scotland and the rest of the UK. Thomas Sampson (London School of Economics) will discuss these issues in his article. As the experience of Ireland has shown, it is possible to shift relative trade priorities to new markets, but such changes take time to materialise.

A fourth key set of issues revolves around preferences for greater levels of autonomy and powers to do things differently vis-à-vis economies of scale and ‘pooling and sharing’.

Proponents of Scottish independence argue that it would provide greater opportunities for policies to be better targeted to the strengths of the Scottish economy, helping to improve economic performance over the longer term. They often point to the successes of small independent countries elsewhere in the world, many of which have higher living standards than the UK. There are a number of areas where the Scottish economy is different to the UK, such as in demographics and the sector mix of the economy, so a different policy approach might be an advantage. Ewan Gibbs (University of Glasgow) discusses how debates about Scottish independence have become interwoven with our understanding of deindustrialisation in Scotland in recent decades.

Figure 5: Percentage population change, 2000-2020

Source: National Records Scotland

Figure 6: Projected population change, 2020 to 2045

Source: National Records Scotland

Figure 7: Industry composition in Scotland

Source: Office for National Statistics, authors' calculations

Opponents of independence argue that while some (or all) of this might be true, in the modern global economy, all national economies operate under constraints and that Scotland gains from being able to tap into UK-wide resources that strengthens its economy.

Proponents of independence also frequently argue that Scotland’s interests – over the long term – might not be best served in a UK economy that has high levels of inequality (both by income and spatially).

Opponents counter that the devolved Scottish government already has substantial levers to influence day-to-day activity in the Scottish economy. What this suggests – and this is covered in an article by Andy Cumbers, Bob McMaster (both University of Glasgow) and Sheila Dow (University of Stirling) – is that a political economy perspective might provide insights beyond simply looking at current data.

Many of these debates owe their origins to the fiscal decentralisation research on the trade-off between decentralised versus centralised decision-making and studies on the ‘optimal size of nations’ (Oates, 1999; Alesina and Spolaore, 2003). Economic history too points to important work on ‘persistence’ that has so far largely been ignored in debates about Scottish independence. It suggests that constitutional or political change does not always bring immediate shifts in policy choices or economic performance as many ‘legacy effects’ can act as a constraint (Muscatelli et al, 2022).

Many of these debates have implications for elsewhere in the UK, and colleagues in Northern Ireland (Graham Brownlow, Queen’s University Belfast) and Wales (Calvin Jones, Cardiff University) will reflect on what Scottish independence might mean for them. David Bell (University of Stirling) will review what options might be possible for greater fiscal decentralisation in the UK.

Finally, there is a discussion about institutions and which ones an independent Scotland would need to establish. Scottish taxpayers already make a contribution to UK-wide institutions. So some of the cost of new institutions required under independence could be offset (in part or in full) by not paying for UK equivalents.

Arguments typically take place over whether any losses of economies of scale (cost-savings from creating larger institutions) are likely to be better or worse than any gains in efficiency and reduced complexity. Tim Besley and Chris Dann (London School of Economics) will discuss issues of fiscal capacity and Gemma Tetlow and Thomas Pope (Institute for Government) will discuss the different institutions of economic policy that an independent Scotland would need.

What has changed since 2014?

One obvious question that people ask is: if decisions over independence are for the long term, what could have changed in the last eight or so years? The answer is quite a lot.

For example, economic conditions have changed since 2014. Like many policy areas explored at the Economics Observatory, the Covid-19 crisis puts an imposing backdrop on debates around Scottish independence – not least on the timing of any referendum. As has been the case around the world, the pandemic resulted in a significant shock to the Scottish economy. At the peak of the lockdown in 2020, GDP fell by over 20%.

There is some evidence that the Scottish economy might be coming out of the Covid-19 recession slightly more slowly than the UK as a whole, but it is difficult to reach any firm conclusion at this stage. But what is more important is that over the last decade, Scotland’s economic performance has been weaker than that of the UK as a whole.

The decline in North Sea oil and gas production is a key factor here. In addition to creating a weaker economic backdrop for Scotland’s economy, oil revenues – which were forecast during the last referendum to raise around £7 billion per annum – are now on track to raise only around £1.5-2.5 billion per annum for the foreseeable future.

Political conditions have changed too, of course. For example, the Scottish Green Party – which disagrees with the SNP on aspects of Scottish independence, including currency – now have two ministerial posts in the Scottish government.

In addition, and as highlighted above, Brexit has changed much of the political context. But as mentioned, this poses some challenging questions about any transition process, as well as throwing up some new opportunities over the long term. John Curtice (University of Strathclyde) will talk about the latest polling on independence in his article.

Conclusion

We hope that this series proves informative for readers. There will be some issues that you will no doubt agree with, some that you will disagree with. But that’s the value of informed debate. We hope that whatever your views on Scottish independence, the articles in this series help to inform you about where and how you can find more information.

Where can I find out more?

- Scottish Government Economic Statistics

- Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland

- Scottish Export Statistics

- Scotland’s Future: Scottish Government 2013 White Paper

- Scotland analysis papers: summary leaflets from the UK Government

- What Scotland Thinks?

- The Scottish National Party’s Economic Prospectus for Independence: Out with the Old?

Who are experts on this question?

- Anton Muscatelli

- Nicola McEwen

- National Institute for Economic and Social Research

- Fraser of Allander Institute

- Institute for Fiscal Studies

- Institute for Government