Does anybody prefer the state of the world now to how it would be with no pandemic? It seems clear that the severe restrictions on daily life and the risk of getting Covid-19 far outweigh any possible gains, except for a very few people.

When economists ask who is better off as a result of a change of circumstances in society, we do not mean simply who has more money: we mean who has more ‘utility’. Someone is made better off by coronavirus if they prefer the state of the world today compared with the state of the world had the pandemic not occurred.

Covid-19 has imposed very big constraints on almost everyone’s life – we’ve had strict limitations on seeing our families and friends; and we haven’t been able to go to restaurants, travel or undertake many other activities that used to be part of daily life. We typically think that constraining what people can do makes them worse off because they can no longer enjoy the utility they got from doing the things they like to do.

In addition, most people are considerably worse off financially because they have lost their job, lost access to goods and services they have already paid for (for example, cancelled holidays), suffered a reduction in the value of their assets (for example, houses in many parts of the country are now worth less than they were before the pandemic) or experienced other losses of income.

Most importantly perhaps, is the fact that everyone has experienced a significant increase in the risk of getting seriously ill or dying, have loved ones who have become ill or died, or have watched the rest of the world experience such losses. These are large losses in terms of people’s wellbeing and enjoyment of life.

Even for people who have not experienced losses directly, there is likely to have been considerable disutility from worrying about people in their communities and in the larger population. It is difficult to put a monetary value on these losses, but it seems likely that for almost everyone, the losses will significantly outweigh any gains that they may have experienced.

People do, however, report some gains. For example, data on people’s opinions and lifestyle (Office for National Statistics, ONS, 26 June 2020) report that almost half (43%) of adults said that some aspects of their lifestyle had changed for the better since the pandemic started – because they were now able to spend more quality time with the people they lived with, enjoyed a slower pace of life and preferred that they were spending less time travelling.

Another study reports that many parents feel that their relationship with their children has improved during lockdown (Understanding Society, 2020).

The assertion that most people are probably worse off is based on the assumption that the losses that they experience from the deaths and illness caused by the pandemic are large. It is also based on the assumption (common in economic models) that constraining what people can do makes them worse off.

Do constraints on people’s activity always make them worse off?

Why do we think that constraints on people’s choices make them worse off? Put very simply, if we see someone walk into a room and there is an apple and an orange on the table and they choose the apple, then we think that this reveals that they prefer the apple to the orange. They had a choice and they chose the apple over the orange.

In many situations, this is a reasonable way to think about the world. In the current context, if people could freely choose how they wanted to spend their time and money before the pandemic, then why didn’t they choose to spend more time with family, live a slower paced life or travel less. We assume that the fact that they didn’t make these choices reveals that they liked to do the things that they were doing.

But it’s also possible that people got into bad habits, committed themselves to do too much or did things that they didn’t really want to do. This could be because they didn’t have free choice: for example, someone might not like their daily commute and prefer to work from home, but before the pandemic, their employer required that they come to the workplace.

If it was the case that people’s choices were not always made freely, then their observed behaviour might not reveal what they prefer to do. In that case, they could be made better off by the pandemic – at least in this dimension.

There are some situations where we think that imposing constraints can make people better off, but they are not the norm. One situation where this might be true is if someone was previously making bad choices that they regretted, so the choices gave them disutility.

This could be when people get into bad habits. For example, there is some evidence that people might have bad habits over the choices of food they eat (Cherchye et al, 2020). Perhaps being forced to eat at home all of the time has made some people better off because it breaks those bad habits and leads them to eat healthier foods.

Another situation where some people could be made better off by the restrictions would be where what someone enjoyed was something that was not entirely within their control. An example would be if a parent likes it when their teenage children stay home and interact with them, but that is not what the teenagers would choose to do. The government forcing teenage children to stay home would make the parents better off (though not necessarily the teenagers).

There are also circumstances where collectively it seems clear that we are making bad choices: polluting the environment is a clear example. Legislating that people can’t drive or fly has probably led to environmental benefits that many will enjoy.

But while many people may have enjoyed these benefits, it seems unlikely that, faced with the choice of incurring the costs that the pandemic has exacted on society versus the environmental benefits we have experienced, many would choose the pandemic. So in that sense, we can infer that they are not made better off overall.

Nonetheless, it could be that the pandemic has changed the nature of the policy debate, and that more radical policies towards the environment now have a greater chance of being considered. That remains to be seen.

Related question: Can policy steer us towards a greener and fairer recovery?

In addition, it is important to remember that many people are very badly affected by the constraints that have been placed on daily activity. For example, there is a reported increase in mental health problems (Banks and Xu, 2020) and a rise in domestic violence (BBC, 12 June 2020). This might have a negative impact not only on those individuals, but also on others in society who care about these people (whether they know them or not).

Who might have gained financially?

The fact that we have seen an unprecedented fall in GDP tells us that most people have been made worse off financially.

Related question: What will be the impact of the crisis on household finances?

But there are some people who have gained financially. A small number of people might have gained so much financially that it is plausible that these gains have offset the increased risk of illness and death (and perhaps for some of the very rich the legal restrictions on activities have had only a modest impact).

For example, the founders of Zoom, Facebook and Amazon all saw their net worth increase by many billions, because of the stock market performance of their firms (businessinsider.com). Whether they were made better off overall would depend largely on how much disutility they got from the fact that the rest of the world was suffering.

Related question: How have Big Tech and other digital platforms fared in the crisis?

Overall, tech companies and some pharmaceutical companies look to be performing well (Financial Times, 19 June 2020). Firms in some industries are selling a lot more too, for example, the large supermarkets. During lockdown, people were not allowed to eat out, so they switched to purchasing much more of their food eat from supermarkets.

While this led to increases in the revenues that supermarkets received, it does not necessarily translate into increased profits, because at the same time the cost of supply of some goods and services has been increasing. Articles in the Financial Times on 2 July 2020 and 23 July 2020 report the large supermarkets all saying that additional costs, mainly staffing costs, mean that increases in profits will be modest.

Internet service providers, media companies and telecoms services have all experienced increases in demand – more people working from home, having virtual meetings, using cloud services and logging in remotely – and more people staying at home streaming movies and playing video games.

But these industries also rely on income from advertisers, which has fallen markedly – with some estimates suggesting that advertising expenditure in the UK will be £4 billion less in 2020 than in 2019 (WARC, 30 April 2020). How these two factors balance out remains to be seen.

The video gaming industry has possibly fared better than most. It has seen large increases in demand – and the impact on the costs of supply has been small, as it is relatively easy to work from home.

But even in this industry, we see some negative impacts, due to the cancellation of trade shows and restrictions on travel. People working in this industry are not better off because of the pandemic, but they are relatively less badly affected than workers in other industries.

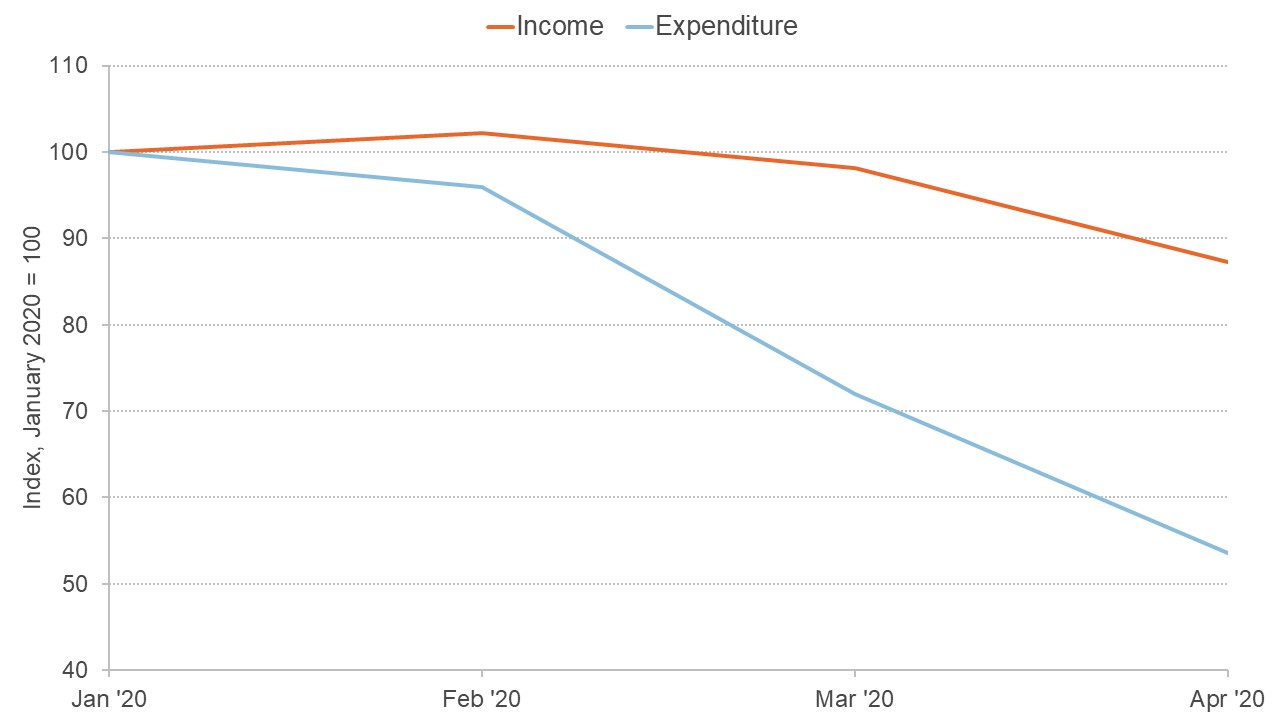

It also looks like people are saving more, on average. Figure 1 is based on bank account transaction data from a large financial technology company in the UK. It shows the average monthly expenditure and the average monthly labour income for a sample of UK households up to April 2020, relative to their levels in January (Hacioglu et al, 2020). Expenditure has fallen much more sharply than income, suggesting that savings will have risen.

Figure 1: Average income and expenditure in the UK

Source: Hacioglu et al, 2020.

Related question: Is the Covid-19 recession caused by supply or demand factors?

Data from the ONS point to an increase in the household savings rate, but they also make clear that by historical standards the savings rate is still lower than during many other periods in the past 50 years.

Some of this will be a genuine financial gain, for example, people who typically have to commute to work will now not have to incur the costs of that commute. In fact, reductions in commuting might have saved more than just money, with some evidence that lengthy commutes lead to reductions in health and happiness (Prospect magazine, 2019).

But people are saving mainly because they are constrained from spending. They would like to go out to restaurants, cinemas, sporting events, etc., but they have been legally constrained from spending their money in these ways.

This means that people are less well off than they would be if the pandemic had not happened. They might be relatively better off than people who have lost income and so are not able to save, but we can’t say that they are better off from the pandemic.

Overall, we don’t have the data to be able to quantify exactly who has gained, and by how much. But it seems likely that for most people, any financial gains, or any gains from enjoying time at home, will not be high enough to offset the considerable losses from the pandemic.

Where can I find out more?

The Wikipedia page on revealed preference theory gives an accessible introduction to the economics behind economists’ use of observed choice to impute people’s preferences.

Data from the ONS suggest that some people are enjoying some aspects of their life during lockdown.

Data showing that mental health has worsened over the pandemic are discussed in a report by James Banks and Xiaowei Xu.

Who are experts on this question?

- Andrew Oswald, University of Warwick

- Nattavudh Powdthavee, Warwick Business School

- Paolo Surico, LBS

- Xiaowei Xu, IFS