As lockdowns have changed the ways in which people spend their time and money, many have made a priority of engaging with the local natural environment. This has led to investments in nature, increases in wildlife populations – especially birds – and improvements in wellbeing.

Since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, people across the world have endured extended periods of lockdown. Through these intermittent phases of economic suppression and closure, expenditure habits have changed substantially.

Naturally, this has included a greater shift to online shopping and purchasing products that can be enjoyed at home, while holidays, travel and indoor social activities have fallen by the wayside. These changes to our leisure-based spending relate both to periods of lockdown and to planning activities when making the transition away from times of restriction.

One notable development has been an increase in purchases of products that enhance our ability to spend more time engaging with ‘backyard wildlife’ (Clucas et al, 2015). Data from both the UK and the United States show that interest in bird tables, bird baths and bird food grew significantly through the major periods of lockdown that began in March 2020.

Not only do these trends provide an economic boost to associated industries, but they also have the added advantage of improving survival opportunities for bird species, many of which have faced considerable population decline in recent years through habitat loss.

This increased engagement with nature also contributes positively to individuals’ wellbeing. At a time when society is forced to segment and isolate, deeper engagement with the natural world offers a new form of interaction from which people can establish feelings of connectivity and purpose.

How have people invested in local nature during lockdowns?

Akin to many household-based leisure pursuits that have enjoyed increased popularity through lockdown periods, people intensified their engagement with backyard wildlife in 2020.

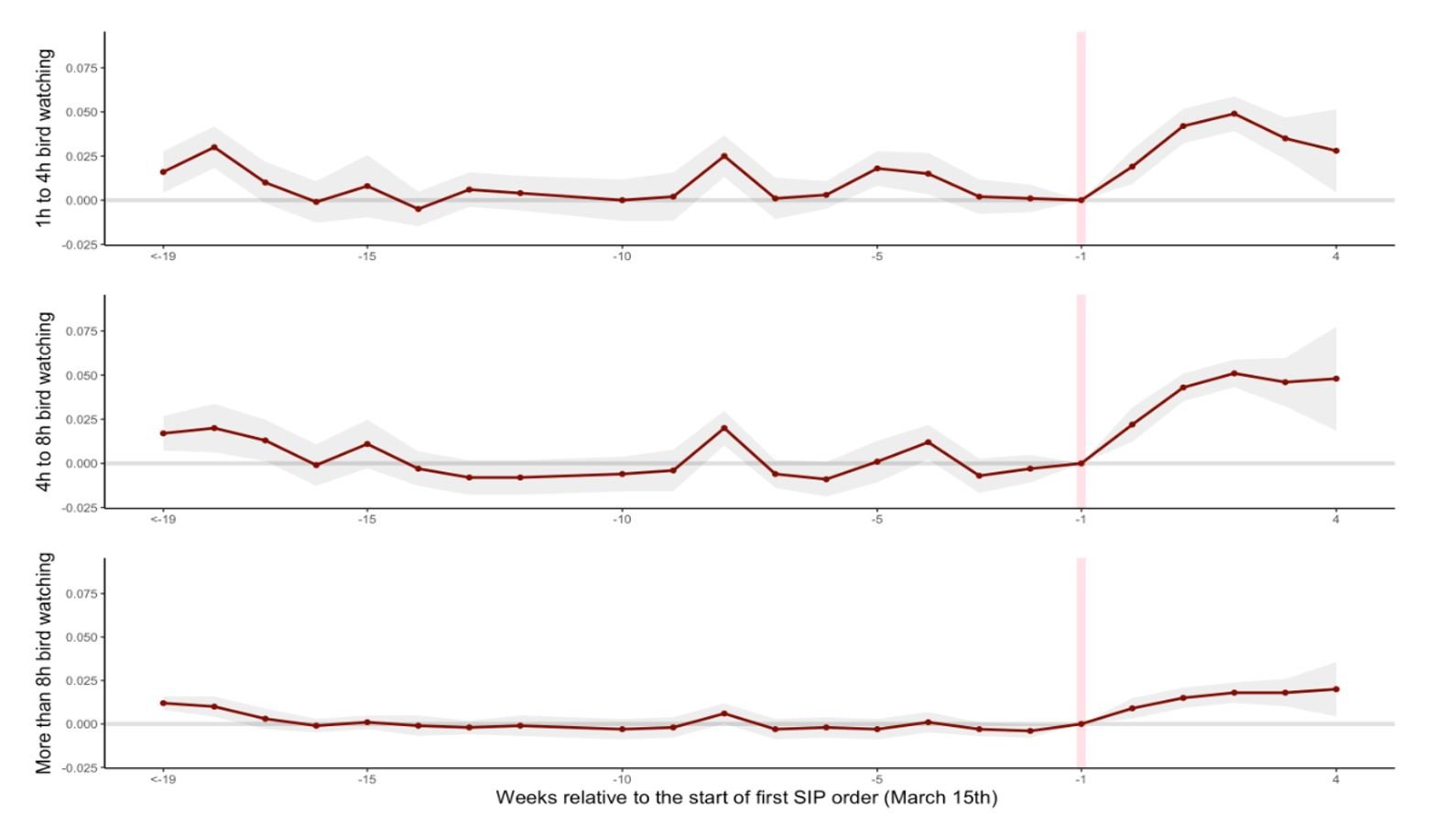

This has occurred in two ways. The first is through time spent connecting with local wildlife. Figure 1 shows changes in the time people spent watching garden birds pre- and post-lockdown. This seems to follow a pattern of ‘shifted’ intensity across the spectrum. In other words, this raised interest occurs with both those with little previous engagement and those with a considerable prior interest.

Figure 1: Trends in time watching birds

Source: PFW Data (Nov - Apr) 2015 – 2020

Note: SIP refers to shelter in place

The second relates to online shopping searches for wildlife-friendly goods. The frequency of the searches for bird tables, bird food and bird baths all increased significantly following lockdown announcements, as shown by Figure 2.

Figure 2: Trends in search terms

Source: Google Trends, 2016 - 2020

Although we cannot verify whether the conversion of ‘search to purchase’ is consistent pre- and post-lockdown, the chronology of events is certainly interesting from the perspective of consumer behaviour. Initially, it appears that people display an interest in attracting local wildlife to their area, and they do so through buying food and tables.

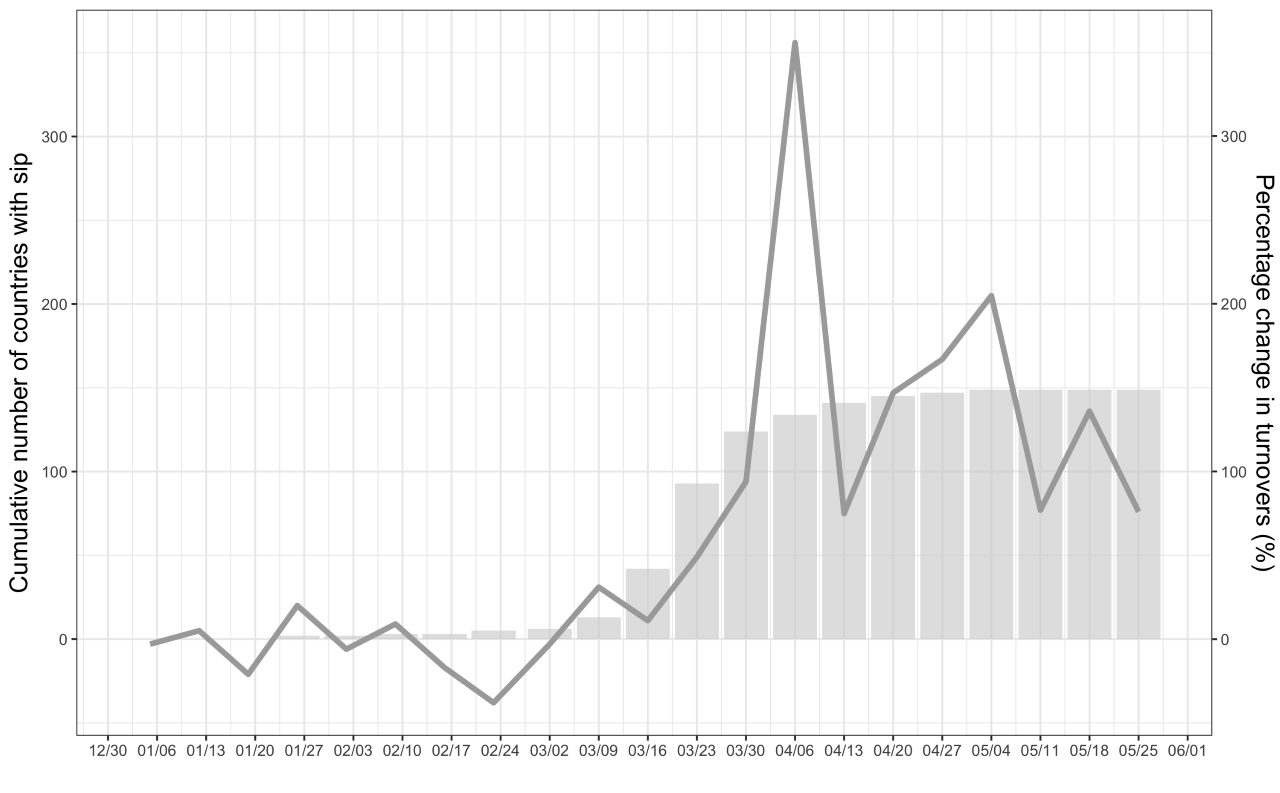

Next, and indicated by data from Spiny Software shown in Figure 3, people look to identify species. A spike in related app purchases in April 2020 fits this timeline.

Figure 3: Changes in year-on-year bird identification app downloads

Source: Spiny Software (Dec - Jun) 2018 - 2020

Finally, people enhance their relationship with nature through their search for products that offer nesting and watering opportunities.

These data trends are useful to consider from an economic standpoint, but also shed light on people’s behavioural psychology when engaging with these types of activity. Our conjecture is that this sequence of ‘feed-identify-nurture’ is consistent with cognitive processes people undertake when investing in networks. It demonstrates the necessary first steps that individuals take to forge long-lasting connections with the environment on their doorstep.

What are the implications for bird populations?

While we believe that the motivation for engaging with local wildlife is largely anthropocentric, evidence does suggest that people are concerned about both species’ welfare and the general health of their local environment (Schuetz and Johnson, 2019; Brock et al, 2017). From an economic standpoint, bird feeding can certainly be classified as an action that delivers both personal and wider benefits.

Research indicates that contribution intensity is greatest when there are complementarities between these private and public motives (Cornes and Sandler, 1994; Vicary, 1997; Lefevbre et al, 2020). Habitat loss is causing a decline in local wildlife populations, in particular through brownfield development and changing urban planning structure (Stanton et al, 2018; Rosenberg et al, 2019). Therefore, the boost to avian populations from feeding (the public element) arguably induces greater enjoyment (the private element) because people can see bird populations arriving and thriving in their local area.

Studies indicate that for actions to offer long-lasting benefits, they should involve routine and repeated interaction. Urban feeding typically delivers birds in greater numbers and with improved regularity. It thus fulfils these criteria, while also providing a crucial boost to the species themselves during winter and breeding seasons.

One unanswered question is the trade-off between the variety and stability of bird populations. Supplementary feeding will usually be most beneficial when it supports a significant population of the same species. This would give greater opportunities for breeding and more resilience within that particular population.

Yet we can assume that those feeding birds value variety and the thrill of seeing a range of species that visit their bird tables. This raises concerns about the long-term effect of an elevated interest in lockdown feeding. The propensity for people to become disengaged does need to be taken into account when assessing the true environmental benefits created.

What is the impact on people’s wellbeing?

Engaging with backyard nature has been identified as beneficial to long-lasting life satisfaction. Those studying subjective wellbeing highlight several qualities that immersion in nature offers. ‘Interconnectedness’ is one such example and is an emotion common to many wellbeing-enhancing actions, including involvement with religion, community and wider society (Frey and Stutzer, 2010; Dutcher et al, 2007).

Furthermore, the repetition associated with ‘everyday wildlife’ interactions can induce positive feelings of responsibility, routine and the achievement of success under uncertainty (Rappe, 2005; Jacobssen et al, 2008; Diener and Biswas-Diener, 2008; Dolan et al, 2008).

When applied to bird feeding, this mix of benefits is described as the ‘warden effect’ (Brock et al, 2017). This differs somewhat from the type of value we assume that people derive, say, from donating to environmental charities – where we believe that people donate because doing so evokes feelings of ‘pro-sociality’, or they perhaps have an existence value for the species (that is, they like the notion of it being preserved for future generations).

Instead, displaying ‘warden tendencies’ elicits a value more closely resembling those we derive from our domestic pets or from gardening, because it involves a repeated connectivity that delivers routine, reassurance and purpose within our lives.

If one accepts this concept, then the value that people derive from more pro-active engagement with backyard wildlife is particularly important during a global pandemic. This is particularly the case as many of the other avenues through which people find connectivity, responsibility and interaction are no longer accessible. These include sports club participation, religious attendance and visiting family members.

Even if only temporary, this implies that a rise in the uptake of local environmental activities not only fills leisure time, but also simultaneously improves individuals’ wellbeing through the feeling of usefulness that this allows within their community.

Conclusion

Covid-19 has brought health, economic and social challenges at local, national and global levels. Amid these difficulties, engagement with local wildlife may have offered a ‘triple-win’ during periods of lockdown:

- Economically, searches for and sales of products associated to wildlife-friendly gardening provide a welcome boost to their respective suppliers.

- Ecologically, this increased support for backyard wildlife offers benefits to the individual and more widely, by counteracting the historical long-term species decline that has occurred through habitat depletion.

- Socially, the characteristics of this engagement can evoke ‘warden-style’ feelings for the individual. This may deliver an important substitute for the routes by which this wellbeing was formerly derived, given that these are restricted or prohibited in lockdown.

Whether these habits persist when we emerge from lockdown periods remains largely unknown. Nevertheless, given the nature of Covid-19, countries continue to find themselves in a fluid state with social restrictions as virus cases rise and fall. In such an environment, local wildlife could play a vital role in filling our desire for interconnectivity. In addition, the resilience of these species without human aid means that they will be around for people to enjoy as and when they wish.

Finally, although our local environment contains some components that remain constant (for example, the locations of green space or the wildlife you expect to find there), seasonality brings different opportunities. A lockdown in the spring affords people the chance to see fledgling birds and install man-made nesting sites; in summer, the requirement to refill water resources; and in winter, the need to provide vital sustenance to hungry species.

As a result, engagement with local wildlife throughout a pandemic not only occupies our leisure time, but also offers us diverse ways in which we can feel useful, connected and valuable.

Who are experts on this question?

Public goods

- Richard Cornes, Research School of Social Sciences, Federalism Research Centre, Australian National University

- Todd Sandler, Department of Economics, Iowa State University

Nature and happiness

- Ed Diener, University of Utah and University of Virginia

- Robert Biswas-Diener, Portland State University

- Daniel Dutcher, Clean Energy Group,

- James Finley, Pennsylvania State University

- A.E. Luloff, Pennsylvania State University

- Janet Buttolph Johnson, University of Delaware

- Mike Brock, University of East Anglia

- Jacqueline Doremus, California Polytechnic State University

- Liqing Li, California State University, Fullerton

Where can I find out more?

- Wild bird feeding in an urban area: intensity, economics and numbers of individuals supported: Report by Melanie Orros and Mark Fellowes in Acta Ornithologica.

- Lockdown leads to ‘cleaner air, more wildlife and stronger communities’: ITV News report in April 2020.

- Coronavirus: Only 9% of Britons want life to return to 'normal' once lockdown is over: Sky News in April 2020 reports that people have noticed significant changes during the lockdown, including cleaner air, more wildlife and stronger communities.