Supporting the fishing industry after Brexit; deciding how university places should be allocated based on young people’s exam results; putting a value on human life to inform decisions about healthcare or lockdown – current examples of the complexity of effective policy-making.

Newsletter from 29 January 2021

It being Friday, the main course in this week’s newsletter is fish. And if you’re going to talk about the economics of fish in the UK, you’d better start with Scotland. It’s the country’s piscatorial powerhouse, making up almost two-thirds of UK output.

Share of UK gross value added in fishing and aquaculture by UK country, 2018

As a new Observatory article by Graeme Roy and Stuart McIntyre explains, the Scottish fishing industry has faced a tough start to the year, largely the result of the post-Brexit trade deal.

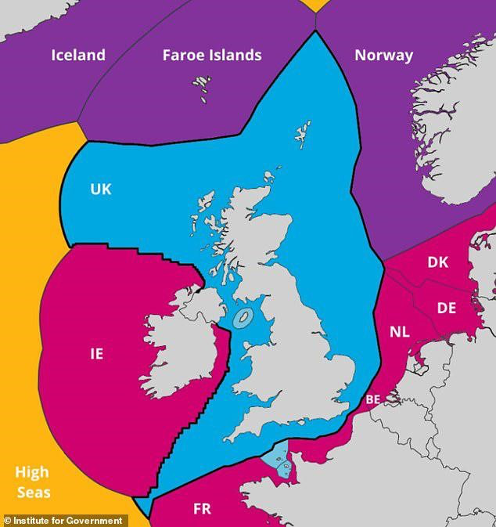

The UK’s waters, set out in the map below, are productive. They account for around a quarter of the value of fish landed by EU member state vessels in the North Atlantic, with the main EU players being France, the Netherlands and Denmark.

UK fishing waters

The value of UK waters means that access is highly coveted, which helps explain why fish became a fault line in the final stages of negotiating a new trading relationship. The resulting EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement is 1,449 pages long. Skimming it alongside our more manageable article, three things jump out.

First, the sheer complexity. The monster document, translated into 24 languages, shows why trade deals take so long. A search for ‘fish’ returns 368 results and that is just the start. The market analysis is split out by species and the sea in which they swim. As well as detail on haddock and row after row of catch data (cod have five entries, sole boast seven), there are reams of analysis on weird and wonderful sounding fish: horse mackerel, great silver smelt and the western spurdog. The plight of the roundnose grenadier, a deep-sea fish first ignored then almost fished out of existence, is an economic tale all of its own.[AL1]

Second, the emergence of a sensible plan. As Graeme and Stuart explain, despite all this complexity, the fishing deal comes down to two things: access to waters and access to markets. The trade deal prevented the imposition of high tariffs (taxes on exports could have been up to 25%) and sets out a gradual decline in EU access over the next five years. Sudden shocks – via spiking prices or slashed quantities – are, in theory, averted.

Third, the tough reality of trade. The problem with the plan is that modern trade barriers are more subtle than tariffs and quotas. They work through red tape, as the World Trade Organization explains here. Post-Brexit, Scottish fishers have been caught in new net of customs checks, certificates and declarations. These, so-called ‘non-tariff barriers’ can grind trade to a halt. Scottish firms have seen crates of crabs and lobsters sitting in ports for 30 hours. The future for these firms, particularly the smallest, is uncertain, as Graeme and Stuart explain.

What value to put on a life?

The complexity of designing policy extends to other big questions that current circumstances have thrown up. The biggest of all is how to value life, discussed byRebecca McDonald of the University of Birmingham in thought-provoking new Observatory article.

The starting point for the analysis is that when making a policy decision – from the value of a new medicine to the cost of lockdown – a measure of the value of a life may be needed. There are various options:

- The ‘value of a statistical life’: the monetary value we put on someone’s life. A related Observatory piece reports that this is put at £1.53 million in the UK (2010 prices).

- The value of a life year: if a shock or policy has a differential effect by age, policy-makers might want a measure that reflects this. In such cases, the life of a young person or child may be more highly weighted that the death of an octogenarian. The current UK value is £60,000 per year.

- Quality-adjusted life years: the idea here is that a year of robust living should be valued more highly than a year spent in ill health. This measure is used by the NHS, with numbers as low as £15,000 per year.

Putting aside the brutal logic of all this, there are still huge problems. First, the variance in the numbers used is shocking. Joanna Coast and Sabina Sanghera report that one 2016 study finds a range of €1,000 to more than €5 million per life year. Making reasonable policy choices when the inputs are so wide seems impossible.

Even if a sensible number could be found, Rebecca’s article explains the difficulty in using it as a practical tool for policymaking. The metrics each rely on the idea that more – whether that’s more lives, more years or more quality – is better. But these simple sums don’t always line up with people’s ethical choices.

One example is the ‘moral machine’ test that almost 40 million people from 200 countries have taken. (You can try it here: www.moralmachine.net). Participants are asked to tell an autonomous car what to do when faced with tough choices – for example, hit a wall, which leads to the driver’s death, or swerve and kill a pedestrian. The results reveal our moral inclinations: law-breakers tend to get mown down in the simulation, even if young. Women are more likely to be spared than men.

Another shortcoming of the ‘valuation’ approach is the importance of fairness. Rebecca’s own research shows that people have strong preferences for an equitable policy. They want even-handed rules and regulations, even when these lead to a higher number of overall deaths. This means simple sums should not guide policy. The article explains in more detail and sets out a route forward.

I predict a riot

Sometimes an article contains a fact so stark that it makes you rethink policy completely. For nearly 60 years, Britons aiming for university have filled out UCAS forms (UCCA forms in their original, 1961, incarnation). The deadline for these applications is today. Universities then make offers based on predicted grades. These guesses are important: they can influence a young person’s life. But they are made by teachers that know the kids, and the exams, very well. So, how good are teachers’ crystal balls? An unrepresentative poll of two people in our house agreed that 80% accuracy would be decent, and 70% acceptable.

The real number, highlighted in an Observatory piece by Lindsey Macmillan and University College London colleagues, is 16%. This casts doubt on the entire system. The biases are depressingly obvious. Teachers systematically over-predict results, except for kids from poor backgrounds, who get predictions that keep them out of top universities.

An overhaul is clearly needed, and the authors propose a system of post-qualification admissions, or ‘PQA’. The school year would change, with a short, sharp exam period in May. Kids would then stay on until July, receiving grades and applying on the basis of hard data rather than their teachers’ woeful clairvoyancy.

The policy is set out in detail and it is convincing. The only wrinkle I can see is the 18-year-olds themselves. At my own further education college, telling kids they had to return to the classroom after their last exam would have resulted in a ruck. As all the pieces this week show, making good policy is a tough challenge.

Richard Davies, Director