Environmental policies like carbon taxes can hurt poor households and small businesses. Careful policy design can transform a trade-off into a double dividend.

Unabated climate change will not only damage our natural world, but also have a significant effect on the global economy. Inaction is therefore not an option. But will inequality grow because of decarbonisation policies? And if so, can the negative effects somehow be offset?

Trade-offs

Inequality poses a real risk. If decarbonisation policies are perceived to be unfair or lead to job losses, they will lose public support. This could delay action, which scientific evidence suggests we cannot afford.

Inequality can take many forms. A policy may have different effects on individuals or families with different income levels or across regions. Studies have explored the impact on consumers (their spending on energy as a percentage of total expenditure) and the differences in the ability of large and small firms (including renewable energy producers of various sizes) to thrive under a range of policies. Age too is an important yardstick: policies may affect intergenerational equity. Internationally, energy transition may affect countries at different levels of development.

This body of research suggests that decarbonisation policies can push up inequality in the short and medium term. In particular, policies—including carbon taxes—that support the deployment of renewable energy can result in higher energy prices. This puts a disproportionate burden on poorer households.

Offsetting the downsides, these policies stimulate innovation, allowing firms to gain experience and exploit economies of scale. This has led to big cost efficiencies that now make renewable electricity the cheapest option in most places.

Ten examples include:

- Building codes: Mandatory standards or obligations for building energy efficiency.

- Procurement: Purchase of green and sustainable goods or services by government and the wider public sector.

- Taxes: Carbon or energy taxes that increase the price of fossil-based energy.

- Certificates: White certificates indicating energy savings, which can be traded between regulated firms to achieve government-set energy saving obligations.

- Quotas: Renewable energy quotas that energy suppliers are required to have by national, regional or local governments.

- Auctions: Competitive energy markets in which developers bid for the installation or generation of electricity using a specific technology.

- Trading schemes: A cap on emissions that regulated industries can either meet directly or cover through the purchase of permits from more efficient firms.

- Investment: Public funding for research and development (R&D) that supports innovation in low-carbon technologies.

- Subsidies: Guaranteeing the price for the purchase of electricity (usually above the market price) from renewable energy sources for a specific period —for example, feed-in tariffs.

- Green certificates: Certificates that represent the generation of one unit of renewable energy and which firms can use to meet the obligations.

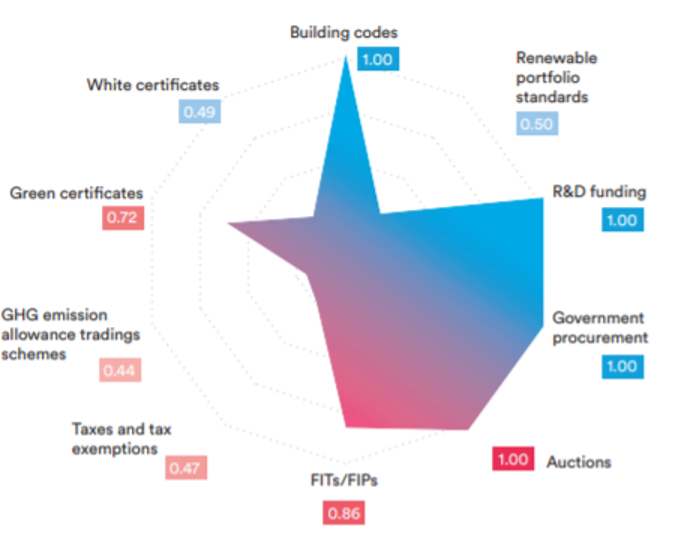

The implications for inequality vary by policy. Tradable green certificates (TGCs), taxes and feed-in tariffs are most consistently associated with increased inequality —they all lead to higher retail electricity prices.

Figure 1: Percentage of impacts on distributional outcomes by policy instrument type

Source: Peñasco et al, 2021

Note: Positive impact (blue), no impact (grey), negative impact (red)

The evidence for consumers shows why it is important to track both the results of studies, and the degree of certainty among researchers. The body of evidence varies by policy (turquoise line): for some levers, there is a rich evidence base, while for others it is sparse. The level of agreement between researchers also varies. For some areas, policy evaluations yield consistent results; in others, results are mixed or inconclusive. The higher the value, the more consistent the evidence of either negative distributional impacts (red) or positive distributional impacts (blue).

Figure 2: Agreement indicator and distributional impacts of ten policy instruments

Source: Peñasco et al, 2021

Note: Blue indicates primarily positive impacts and red primarily negative impacts. The boxes indicate the level of agreement, with 0.33 referring to full disagreement across the studies (half of the studies report positive impacts and the other half negative impacts) and 1.00 full agreement (all studies report impacts in the same direction).

Energy producers of different sizes can be helped or hampered by green policies. TGCs and auctions can also negatively affect small and new energy producers, including wind or solar farm project developers or local utilities. Evidence on renewable portfolio standards is inconclusive. Several analyses find that independent developers are disadvantaged compared with large vertically integrated companies.

Geography matters too. Environmental taxes can have greater negative effects in rural areas where travel distances and lack of public transport mean higher fuel bills. Some studies show that local air pollution taxes—for example, on nitrogen dioxide and sulphur dioxide, both by-products of burning fossil fuels— are fairer than carbon taxes.

Building regulations emerge as equitable policies. This is because poorer households have not disproportionately borne the cost of capital projects or, if they do, they have been compensated through other channels. White certificate schemes have been similar, with the cost burden distributed across society, including energy companies and governments.

There are important gaps in our knowledge. First, the evidence on procurement and R&D is too limited to draw strong conclusions. Second, most research focuses on OECD countries and some large emerging economies (mainly China and Brazil). Third, studies do not consider all the possible impacts of decarbonisation policies—for example, the health costs of air pollution and the damage associated with biodiversity losses are often missing. Fourth, much research focuses on whether certain vulnerable groups have, on some metric, been made worse off. Ultimately, a full analysis across all groups is needed.

Taken together, the evidence shows that some decarbonisation policies can raise prices for consumers and have uneven effects on firms of different sizes. Public opposition to such taxes is a possibility, and will be stronger when the measures are seen as a way to increase government revenues rather than to fight climate change.

To avoid this perception and offset inequality concerns, revenues can be recycled: used to provide social benefits or in-work tax credits for low-income households. The result then would be to stimulate employment and reduce emissions. Careful policy design can transform a problematic trade-off between the environment and inequality into a double dividend.

Where can I find out more?

- Systematic review of the outcomes and trade-offs of ten types of decarbonization policy instruments: Evaluation of technical and socioeconomic outcomes of policy instruments used to support the transition to low-carbon economies

- Decarbonisation policy evaluation tool

- Social impacts of climate change mitigation policies and their implications for inequality: Discussion of social co-impacts of climate change mitigation policy and their implications for inequality

- Equity implications of climate policy: Assessing the social and distributional impacts of emission reduction targets in the European Union: The transition to climate neutrality may modestly increase inequality across income classes; Panagiotis Fragkos and co-authors highlight how lump sum transfers from carbon tax revenue can support household income

Who are experts on this question?

- Dimitri Zenghelis

- Sanna Marakannen

- Benjamin Sovacool