The global financial crisis, persistently weak growth and now Covid-19 have created tensions between politics and central banking. The time is ripe for a refreshed constitution, making clear the purpose of independent central banks, and what should fall to fiscal authorities.

Fifteen years ago, the world of central banking seemed sober, calm and apolitical. Since then the financial crisis, euro meltdown and now Covid-19, together with persistently weak underlying growth, have reinjected politics into central banking, creating dilemmas and tensions.

On the political left, there are calls for ‘People’s QE’ and for central banks to cure climate change and various social ills; libertarians seek salvation in privately issued cryptocurrencies; and the conspiratorialist fringes continue to see monetary officials as in league with enemies of the people.

Whether you cheer or choke on that, there is little doubt that even before Covid-19, something was going on in the once sober world of central banking. Being the only game in town has turned out to be a political, even constitutional, nightmare. Advanced economies need a money-credit constitution – one that makes clear what central banks are for, and recognises our broader constitutionalist values.

Are central banks agents or trustees?

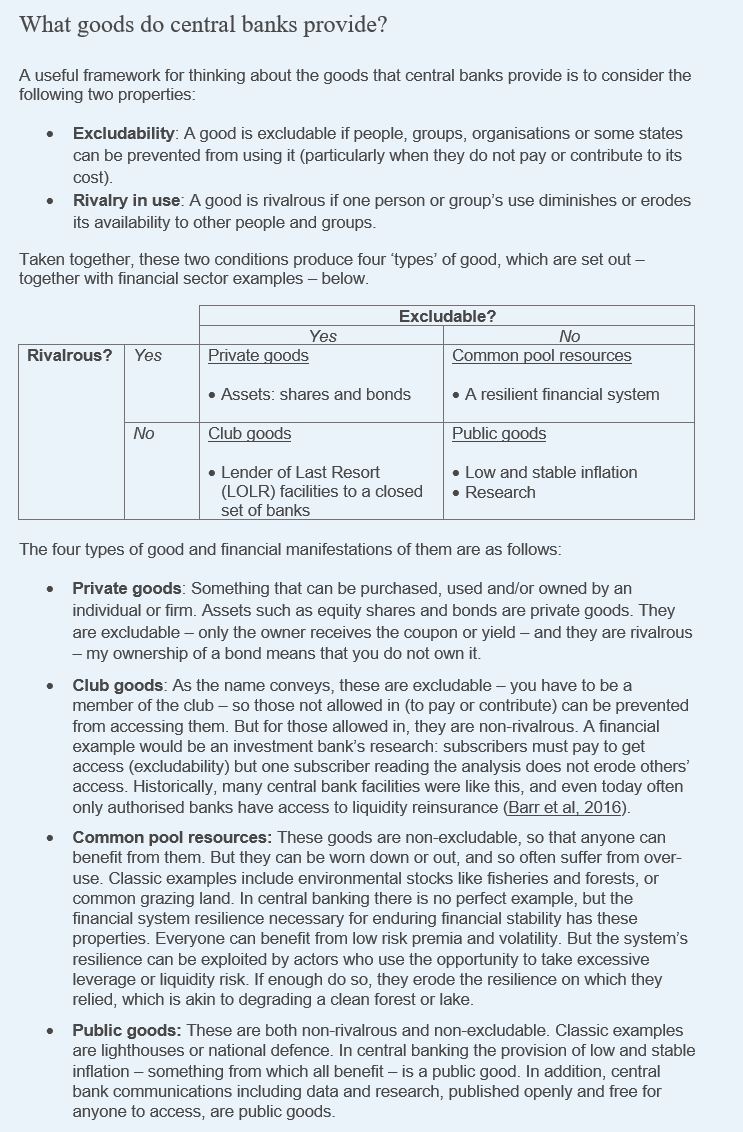

The response to Covid-19 is a reminder that history offers two quite distinct models of central banking. One sees a country’s central bank as the operational arm of government financial policy, its functions shaped by a combination of political expedience and capabilities rooted in being the pivot of the payments system, as Francis Baring put it over two hundred years ago. It effectively underwrites the treasury’s finances and, as the banking community’s team captain, provides club goods in the form of liquidity backstops and policing (see Box). This was the international norm from the 1930s to the 1980s – or, in the UK, the late 1990s.

Under the other model, central banks are independent authorities delegated specific responsibilities and formally insulated from day-to-day politics. They provide public goods (price stability), and preserve common goods that can be enjoyed by all but eroded by the exploitative (financial stability).

Those two modes of existence are so distinct that passage from one to the other – from subordinate agent to independent trustee – is often fraught, with struggles around boundaries, and sometimes disastrous results. In the UK’s case, as the Bank of England sought during the late 1980s and early 1990s to make itself tolerably fit for monetary independence, it voluntarily dropped its involvement in industrial finance, corporate governance, some non-core banking services and all securities settlement services. And yet when, in 1997, independence finally arrived, banking supervision was still transferred elsewhere, with fairly catastrophic effects for the UK in the years leading up to and during the global financial crisis of 2007/09.

The underlying tension here arises from a division of power between treasuries and monetary authorities – between elected and unelected power. The late 2000s crisis was just one of myriad manifestations of this fault line. Since then, around the world finance ministries have decoded the new strategic game – grasping that if they sit on their hands, they can be confident the central bank will stretch ever harder and innovatively to meet its statutory objectives.

(Link to: Barr et al, 2016)

What powers do central banks have today?

That game is predicated on central banks’ extraordinary powers:

- First, the right to create money is always latently a power of taxation, capable of redistributing resources across society and between generations through a burst of surprise inflation (or deflation).

- Second, as lenders of last resort, central banks can potentially pick winners and losers – deciding which banks (and increasingly, non-banks) to lend to in a crisis, and which should be allowed to fail.

- Third, through the terms of their financial operations (collateral, counterparties, etc), they can affect the allocation of credit in the economy.

- Fourth, acting as banking system supervisors, they effectively exercise the delegated powers of secondary law-makers and adjudicators.

Such wide-ranging power needs to be based on and constrained by principles: not only economic principles, but political principles too. Only then will it be possible to judge what role the monetary authorities should have in fighting major problems such as climate change, where it is not yet clear how their powers could be used.

For example, rigorous stress testing of banks’ exposures to climate change would bring forward some of its costs, which could be perverse; while rationing credit to polluters might reduce politicians’ incentives to introduce a carbon tax. Such demonstrations of power could also bring other claims on central banks’ capabilities – for example, wars can also be bad for financial stability, so maybe our unelected monetary officials should ration lending to the arms industry?

To have any chance of navigating these thickets without ending up with rule by central bankers, advanced economies need a money-credit constitution – one that recognises our deep constitutionalist values.

What justifies central banks’ extraordinary powers?

The best, principled case for an independent monetary authority is not merely that, by keeping the state’s promise to maintain price stability, it can deliver better results, vitally important though that is. No, the best argument is rooted in one of the deepest values of constitutional democracy: the separation of powers, which stipulates, among other things, that taxes must be set by the elected assembly, not by the executive branch.

If presidents and prime ministers had discretionary control of the printing press to fund their pet projects and enrich supporters, that would usurp the rights and role of the assembly. Once upon a time, the gold standard acted as the constitutional check, but in full-franchise democracies, we cannot accept the volatility it entailed for jobs and activity.

After the breakdown of Bretton Woods, initially there was no substitute, leading to uncontrolled inflation without compensating benefits in jobs or welfare. Today’s solution has been central bank independence, and it is worth preserving to protect parliament’s prerogatives.

How should central banks be constrained?

But while an arm’s length monetary authority, insulated from day-to-day politics, can help to underpin a constitutional system of government, unelected central bankers need to be constrained by legislation. Their legitimacy depends on it, which matters greatly because legitimacy holds things together when, inevitably, public policy fails the people.

To be accepted as legitimate, central banks’ design and operation must comport with a political society’s deepest political values. If those values are to survive, we need general principles for delegating to independent agencies, including things like being set objectives that can be monitored by legislators and the public, not being given power to make big distributional choices, one-person one-vote committee decision-making in order to avoid rule by one person, publishing operating principles for the exercise of delegated discretion, transparency, public comprehensibility, and a lot more (Tucker, Unelected Power, 2018).

These principles of delegation can guide the articulation of a money-credit constitution centred on the purpose of monetary system stability and imposing constraints on its pursuit:

- For monetary policy: a clear nominal objective, and no autonomous power to inflate away the debt, which is for legislators.

- For balance-sheet operations: keep operations and balance sheets as simple and as small as possible, consistent with achieving objective(s); and any major distributive effects or credit rationing should be cooked into the delegation rather than resulting from discretionary choices.

- As lender of last resort (LOLR): no lending to firms that are fundamentally insolvent or broken (Tucker, 2020).

- For stability policy: as LOLR, the central bank cannot avoid being involved but this should be formalised in law, with a mandate to achieve a monitorable standard for the resilience of the private part of the monetary system as a whole, including shadow banking.

- For microprudential policy: a requirement for banking intermediaries to cover short-term liabilities with assets against which they can borrow from the central bank (Tucker, 2018).

- Across the board: not exceeding powers during an emergency, but an expedited process for legislators temporarily to add powers so long as they are consistent with the core mandate.

- Organisationally: the chair not being the sole decision-maker on anything.

- Accountability: transparency in all things, if only with a lag.

- Communications: speak frequently in the language of the public rather than only of high finance and monetary experts.

- Self-restraint: keep out of affairs that are neither mandated nor intimately connected to legal objectives.

How does the response to Covid-19 fit with this framework?

The past few months seem a world away from all that. In the United States and the euro area, central bankers have again been the de facto actors, because the wider constitutional set-up deprives elected authority of decisiveness, while in the UK it has been difficult to tell whether the Bank of England has reverted to being the Treasury’s operational arm.

Those differences make clear that the pressure points on central banking are going to vary with countries’ fiscal frameworks, making it a mistake to assume that just because the central bank of one big jurisdiction does something, it is fine for central banks in others to follow suit. To take the most obvious example: that the European Central Bank (or to some extent the US Federal Reserve) finds itself substituting for a missing (or unwilling) fiscal authority does not of itself warrant copycat central banking facilities elsewhere.

In evaluating the constitutional politics of their extraordinary measures to preserve our economies – ensuring cash reached households and businesses – it is necessary to discern where each facility lies on a spectrum from independence to subordination.

At one end, the central bank operates freely within its mandate but guaranteed by the finance ministry in recognition of taxpayers ultimately taking the risk (through seigniorage).

Towards the other end, the central bank acts on behalf of government, merely executing the discretionary decisions of the finance ministry, taking no risk itself, and providing monetary financing (directly or indirectly) only if, acting independently, it so chooses. That is the central bank as an arm’s length agent. Beyond lie facilities conducted on the central bank’s balance sheet on the instruction (or forceful urging) of government, and operations conducted on the government’s balance sheet but forcibly financed via the printing press. There are many more variants.

For each point on the spectrum, the test is who is really deciding what. Where independence is in effect suspended, which is not an outrage if the assembly wants to take back control, that ought to be clear, as should be the exit route.

What policies are needed to underpin central bank independence in the wake of Covid-19?

Care is needed if our societies want to maintain the institution of central bank independence as a means for committing to monetary system stability and the fiscal separation of powers. This needs to address two problems: the familiar one of employing central banks to put grit in the way of politicians doing bad things (inflation), but also a new and less tractable problem of politicians ducking what they should do.

Here are five steps:

- An exit route from being the finance ministry’s operational arm back to independence once the pandemic has passed, and defensible decision-making authorities meanwhile.

- Revision of monetary regimes to allow stabilisation policy to operate when the zero lower bound might bite frequently, possibly embracing a higher target for inflation.

- A review of stability mandates, including a general policy regime for shadow banking, a legislated standard for financial system resilience, a statutory bar on lending to fundamentally broken financial firms, and increased independence from the industry. Such a package might have impeded the rash of imprudent deregulatory measures introduced around the world over the past few years, which left trading markets badly overleveraged in March 2020.

- Restraint by central bankers, limiting themselves (when independence is operative) to the mission of preserving monetary system stability rather than offering to solve all society’s problems.

- Widespread vigilance and awareness of subtle but cumulative attempts to repoliticise central banking to serve sectional interests – what is cheered today might bring tears tomorrow. Politics is an opportunistic trade, and there is scant scrutiny of the subtleties of monetary institutions.

My sense is that this package – particularly self-restraint and staying out of politics – will be tough going until the advanced economies adopt fiscal frameworks that put politicians under obligations to do things, as well as constraining them to ensure sustainable public finances in ways that are sensitive to economic circumstances.

This matters – not only in general, but urgently, now – because the best way through the worst economic problems is not to rely almost exclusively on monetary stimulus when rates are at the zero lower bound. Instead, governments should deploy a robust fiscal policy stimulus, with protection against unsustainable excess provided by a truly independent central bank ready to lean against the wind if things go fundamentally awry. Macroeconomic policy has been the wrong way round: we need a strategy that turns on what central banks can do, not on what they cannot.

Whatever the current pressing expedients, which are obviously very real and urgent, it is worth preserving the integrity of our institutions in the longer run. Central banking is one of them, and keeping it in its proper place will provide the incentives for elected power to do what only it can properly do: govern.

Where can I find out more?

- Paul Tucker’s 2018 book, Unelected Power: The Quest for Legitimacy in Central Banking and the Regulatory State published by Princeton University Press, plus many of his recent papers are available on his website.